|

The wheel is the most crucial element of the bicycle: it allows

the rider to roll over the ground with great speed and efficiency. Historians

believe the wheel originated in Mesopotamia sometime around 3,500 BC. While

the Sumerians did not pedal their way through ancient Mesopotamia, animal-powered

wheeled chariots and carts helped haul goods and people for thousands of

years. During the industrial revolution in the 19th century, advances in

materials and engineering made it possible to use the wheel effectively

in human-powered machines. The modern bicycle, complete with a steel frame,

a chain drive, steel wheels and spokes, and pneumatic tires, would emerge

in the late 1800s.

|

The wheels on these bicycles were made of steel but lacked pneumatic tires

(with the possible exception of the boy's bike). Some bikes made for small

children are still made with solid tires. This photograph was taken around

1910.

LIBRARY OF CONGRESS

|

|

|

On the Road

While the use of the wheel was widespread in ancient times,

it did have limitations. The resistance to the motion of a wheel can vary

tremendously depending on the surface on which it is traveling. A rough

road is much harder to roll over than a smooth one. The Romans were aware

of this and developed a massive network of paved roads. While this may have

been the first time in history that roads were improved to facilitate the

wheel, it certainly wasn't the last. In the United States in the 1890s,

cyclists successfully lobbied for improvements in roads nationwide, and

with cycling the nation's most popular sport at the time, legislators listened.

|

|

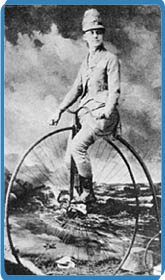

The Ordinary

When most people think about early bicycles, the high-wheelers

of the late 1800s come to mind. These early models had names such as the

"Ordinary" or "Xtraordinary." In England, these bicycles

were also known as "penny farthings" because the large and small

wheels were reminiscent of the large one-penny coin and the smaller farthing

coin.

The pedals were attached directly to the front wheel of

the high-wheelers. The larger the front wheel on an "Ordinary,"

the farther the cyclist would travel with each turn of the pedals. Exploratorium

Senior Scientist Paul Doherty explained, "Every time the pedals would

go around once, that whole giant front wheel would go around once. So, for

one cycle of the bicyclist's legs he might go 140 inches (3.556 meters),

a tremendous distance forward." This made pedaling up hills quite difficult,

but allowed for great speed on the flats.

|

|

BICYCLE INSTITUTE OF AMERICA

|

This image shows an "Ordinary" bicycle. What is somewhat out of

the ordinary is that the cyclist in the photograph is a woman. Although

cycling became quite popular with women in the late 1800s there were still

social taboos associated with it.

|

|

|

|

The Exploratorium's Paul Doherty talks about the early high-wheeled bicycles.

|

|

While the high-wheels were quite efficient, they were

also dangerous: the cyclist was very high off the ground and perched precariously

over the front wheel. So, while the high- wheelers broke new speed and distance

records, they quickly gained notoriety for the dangers involved in riding

them. The slightest obstacle in the road could result in a nasty head-first

fall. "Headers" or "taking a header" were common terms

used to describe an all-too-frequent problem. With a high center of gravity

and narrow tires made of solid rubber (which occasionally could roll off

their rims), high-wheeled bicycles were designed for speed, not for safety.

|

|

|

The Wheel

Page: 1 of 3

Select "Forward" below to continue

|

©

Exploratorium

|