|

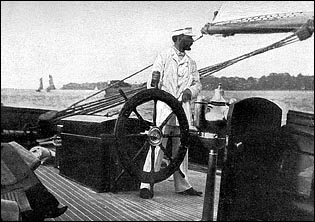

Corona and Coronet: Being a narrative of the Amherst Eclipse Expedition to Japan, in Mr. James's Schooner-Yacht Coronet, to Observe the Sun's Total Obscuration, 9th August, 1896 by Mabel Loomis Todd Houghton, Mifflin and Company, publishers 1898

July 9th. Just a solid month before the eclipse. We did not go

outside last night, the wind having increased somewhat; about ten

o'clock this morning, however, we started for Esashi. It was rough

work rounding the Cape Horn of Japan.

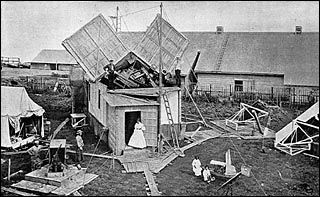

Esashi, July 10th. This has been an eventful day, inasmuch as we have finally reached Esashi, taken possession of our camp, have everything unloaded and under cover.

July 16th. The portable house is about finished outside. The different

tubes for the lenses are being made ready to be bolted on to the

platform, and lots of small work--overhauling and adjusting the

plate mechanisms--is going on.

My duties to-day have been verily like that of Jack-at-all-trades. I have taken up electrical business, connecting galvanic batteries. Then I play carpenter, and screw small boxes on to a wheel; then I paint a lot of square pieces of wood; and from that I go to cutting out regular pieces of black velvet . . . August 3d. Only five more working days before the day that must bring us the Corona or bitter disappointment. [August 9th.] Sunday dawned through a heavy shower. Sunshine succeeded: cloud followed blue sky, northwest wind almost supplanted a damp breeze from the south full of scudding vapor. And still the hours rolled on toward two o'clock and "first contact." The Astronomer had arranged the programme of each person with exactness long before. He still kept calmly at work, giving final directions, the multitude of details resolutely kept in mind with a philosophy as imperturbable as if skies were clear, and cloudless totality a celestial certainty. At one o'clock almost half the sky was blue--two o'clock, and the moon had already bitten a small piece out of the sun's bright edge, still partly obscured by a dimly drifting mass of cloud. Half after two, and a large part of the town was ranged along the fence inclosing our apparatus, once in a while looking at the narrowing crescent, but generally at our instruments, the sober faces in curious contrast to sooty decorations from their bits of smoked glass. And then perceptible darkness crept onward--everything grew quiet. The moon was stealing her silent way across the sun till his crescent grew thin and wan. Shortly before totality . . . Chief and I went over to the little lighthouse and mounted to its summit . . . . Black disks, carefully prepared upon white paper, had been distributed to a number of persons, and several others were ready on the little platform, for drawing coronal streamers. By this time the light was very cold and gray, like stormy winter twilight . . . Grayer and grayer grew the day, narrower and narrower the crescent of shining sunlight. The sea faded to leaden nothingness. The Alger became invisible--sampans and junks faded together into colorlessness; but grass and verdure turned suddenly vivid yellow-green. A penetrating chill fell across the land, as if a door had been opened into a long-closed vault. It was a moment of appalling suspense; something was being waited for--the very air was portentous. The circling sea-gulls disappeared with strange cries. One white butterfly fluttered by vaguely. Then an instantaneous darkness leaped upon the world. Unearthly night enveloped all. With an indescribable out-flashing at the same instant the corona burst forth in mysterious radiance. But dimly seen through thin cloud, it was nevertheless beautiful beyond description, a celestial flame from some unimaginable heaven. Simultaneously the whole northwestern sky, nearly to the zenith, was flooded with lurid and startlingly brilliant orange, across which drifted clouds slightly darker, like flecks of liquid flame, or huge ejecta from some vast volcanic Hades. The west and southwest gleamed in shining lemon yellow. Least like a sunset, it was too sombre and terrible. The pale, broken circle of coronal light still glowered on with thrilling peacefulness, while nature held her breath for another stage in this majestic spectacle. Well might it have been a prelude to the shriveling and disappearance of the whole world--weird to horror, and beautiful to heartbreak, heaven and hell in the same sky. Absolute silence reigned. No human being spoke. No bird twittered. Hours might have passed--time was annihilated; and yet when the tiniest globule of sunlight, a drop, a needle-shaft, a pinhole, reappeared, even before it had become the slenderest possible crescent, the fair corona and all color in sky and cloud withdrew, and a natural aspect of stormy twilight returned. As the beautiful corona lay there in the clouds, a soft unearthly radiance the poetic effect as strong as if in a clear sky, the scientific value lost in vapors, it was still noticeably flattened at the poles and extended equatorially, and must have been of unusual brilliance to show so distinctly through cloud. A few pictures of the blurred corona were taken, if of little practical use, and an interesting experiment for Roentgen rays seemed to indicate their presence in coronal light--a curious result, since they have not been found in full sunlight. The corona, thus safely caught, can now be laid on our tables in manifold representations, and interrogated through the months following an eclipse until the most telling questions for its next coming are plainly evident. |

||||||||||||||||||||||