|

The Total Solar Eclipse, 1900 Report of the expeditions organized by the British Astronomical Association to observe the total solar eclipse of 1900, May 28 A Publication of the British Astronomical Association Chapter VII: "Elche" (Spain) by Mr. E. W. Johnson Leaving England on the 10th May, on board R.M.S. "Egypt" . . . our party consisted of only three members, Lady McClure, Miss Jessie McRae, and myself, but amongst the passengers were some who would observe the Eclipse at other places in Spain.

Elche is an exceedingly picturesque little Moorish town of a distinctly

Oriental type, with white, flat-roofed houses, and surrounded with

palm trees. Our first concern at Elche was to find a suitable observing

station . . . almost opposite [our] hotel was a Café Restaurant,

with a large flat roof, and this we at once engaged, with a stipulation

that no one else should be allowed thereon. This eventually proved

to be a wise precaution, as several strangers on Eclipse day tried

to gain access to it

.

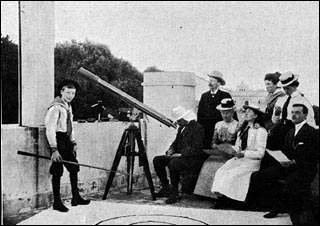

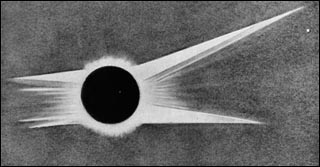

On Saturday, 26th May, we drove to Santa Pola . . . where were established the two British Eclipse Camps, that of Sir Norman Lockyer and that of Professor Copeland. Sir Norman received us very cordially, and explained to us the working of some of his instruments, and invited us to return at 4 o'clock to witness his Eclipse drill. We then visited the Scotch camp about half a mile distant . . . . Whilst we were at the Scotch camp the Governor of the Province of Alicante arrived and was shown the instruments by Professor Copeland. Another object which attracted our attention and which we duly admired was a large wall close by, which had been freshly whitened by the bluejackets of the "Theseus," and was to serve for the observation of shadow bands. After being most hospitably entertained . . . a steam launch met us and took us to the "Theseus," a mile or so out in the Bay. At 3:30 we returned on shore, just in time for Sir Norman Lockyer's Eclipse drill. The apparently simple way in which it was all gone through showed . . . they were quite ready for the Eclipse if it should come a day too soon! The morning of the 28th broke cloudless, and as the Eclipse would not begin till nearly 3 o'clock, we had plenty of time in hand. Close outside the hotel and quite early in the day our attention was directed to some large pictures being exhibited in the streets, representing comets and stars, with dragons and monsters, besides scenes of naval battles, etc., all evidently intended to impress the ignorant peasants, and perhaps deceive them about the great event of the day. The day was kept as a general holiday, and during the morning great numbers of people flocked into the town from all the country round. Shortly before the Eclipse began, it was a curious sight to see the roofs, which until then had been deserted, suddenly teem with life, being crowded with the excited populace. We all kept quiet and cool through the morning, and by 2.30 took up our positions on the roof, when at 2.58 first contact was announced by gun fire. Being all of us provided with dark glasses there was no difficulty in watching the gradually diminishing disc of the sun. At 3.38 Mr. J. H. Willis first announced the appearance of Venus almost vertically overhead. At 20 minutes and 10 minutes before totality I called the times to Lady McClure to make exposures of 10 seconds each for "Gathering Gloom" photographs . . . Soon after the second of these exposures I was able to call the attention of Miss McRae to the rapidly moving shadow bands, and she then made special notes with reference to them. Time was now very close to the critical moment of totality, to which our attention was now completely given, and I was able to see the Corona, as it were, unfold itself some few seconds before a second gun shot announced totality. Miss McRae noted the appearance of planets and stars. My sensitometer exposure being complete, and having some opera glasses handy, I was able to observe the Eclipse itself, and especially noted the polar rays, and was finally rewarded with a splendid sight of Baily's Beads. A second or two of valuable time was lost to us at second contact by someone on a neighbouring roof sending aloft an air balloon which dropped fireworks as it descended, consequently distracting our attention. After totality, shadow bands were again noted, and further departing gloom and sensitometer photographs undertaken, besides photographs of our party in a group on the roof, after which we all returned to the hotel to tea, eagerly talking over together the wonders of the beautiful spectacle we had seen.

Chapter VIII: "Algiers" by Mr. E. Walter Maunder, F.R.A.S. The observers choosing Algiers as their station were far more numerous than those going in any other direction, the ease with which the journey could be made, and the high probability of a clear sky and transparent air, providing a great attraction. But having arrived at their destination, the observers were almost necessarily broken up into several parties. The party with which I was more immediately connected, consisted at starting of Mr. and Mrs. Crommelin, my wife and two daughters, and myself. Very striking looked Algiers, the "White City," as we approached it, its white houses, climbing terrace after terrace up the steep side of the hill, and flashing with dazzling points of light where the sun was reflected back from glass window or conservatory roof. Our hotel was in the very centre of the city, facing its chief Place, a site which in a northern clime would not be ideal for an observing station, but which here in smokeless, fireless, subtropical Algiers had few drawbacks and not a few advantages . . . its roof was thoroughly well adapted for our requirements in an observing station.

On one point our visitors were all agreed, that we had very useful astronomical accessories in the great chimney stacks that rose up to a height of about five feet from the roof, and that we turned them to good account. They made most useful piers or stays for the telescope stands, and their most serious defect was in the presence of the vent, down which it was so easy to drop eye-pieces and screws and other useful or indispensable articles. Mr. Hodge turned even this defect to a good use by making the flue serve as a drop for his telescope weight. The first contact and the progress of the eclipse were observed by projection through the telescope on a sheet of cardboard to avoid fatiguing the eye .

Another observer, Miss Irene Maunder, describes the effect of totality:

"A bell rang and we all hurried to our places, for we knew

there were but five minutes of totality. Another bell--but one minute

more. The sky was deep purple, while over the sea was a strange

light on the horizon, a compromise between a thunderstorm and a

sunset. The colour faded from the sea and trees, a shouting and

wailing arose from the square below, the light was fading; suddenly

the moon slipped over the sun and the eclipse was total. 'Go!' shouted

a loud voice; a metronome began to beat the seconds, and as its

bell rang at each sixth stroke, my sister called the time. 'One!

Two! Three! Four! Five! Six!' There! my photographs were taken,

and now I could look up! I shall never forget the crimson glow,

and above and below it a milk-like flame stretching its long streamers

away into the purple. The darkness, the cold wind, the silent workers

around me, and the shouting crowd below all tended to make this

strange and glorious sight still more impressive, and I found myself

stretching out my arms to that exquisite corona in a perfect ecstasy.

Suddenly the moon slipped off the other side of the sun and out

he shone in a blaze of light, or so it seemed in comparison with

his eclipse. An Englishman cheered. Some Frenchmen clapped. Totality

was over!"

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||