|

|

Sun-Earth Connection Continued Space Weather Forecasts

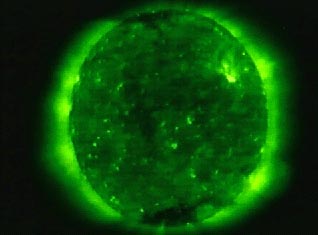

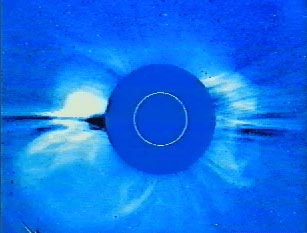

CMEs were first detected by space observatories in the early 1970s. They're difficult to observe from earth, in part because the light given off by CMEs is relatively dim compared to the bright glow of the sun. Even during an eclipse, when much of the sun's light is blocked, CMEs are hard to make out. That's because eclipses provide only a snapshot of the sun, a few minutes at most, and even the most violent, fast-moving CMEs take a half hour to erupt and move away from the sun. What we can easily see from earth are solar flares. These bright flashes of light often precede a CME when super-heated gases in the sun's atmosphere reach temperatures of 10 to 30 million degrees celsius. In the past, solar flares were used to help predict space weather and geomagnetic storms on earth. But they're unreliable predictors, with success rates less than one out of three, says Nancy Crooker, a space physicist at Boston University. That's because CMEs can erupt without a detectable flare, Crooker says. Also, a CME erupting from the side of the sun (from the earth's perspective) may produce a flare, but the shock wave never reaches us. Geomagnetic storms on earth can only occur when a CME heads straight for us. These are called "halo" CMEs because they form a ring around the sun that looks like a tire. Once a halo CME erupts, it takes two to three days for the magnetic plasma to reach the earth.

Halo CMEs are the hardest to detect, but Crooker and her colleagues have identified the signature of halo CMEs on the sun's surface. Now, a fleet of ten space-based observatories run by an international team of space scientists are keeping an eye on the sun in the hopes of providing an early warning system for geomagnetic storms. From December 1996 to May 1997, the SOHO satellite successfully detected nine of twelve known space storms, vastly improving the forecast accuracy. With advance warning from reliable space weather forecasts, power companies, space-walking astronauts, and satellite operators can prepare for impact and minimize damage from CMEs. |

|

|

|