|

The

Sun-Eating Dragon

Continued

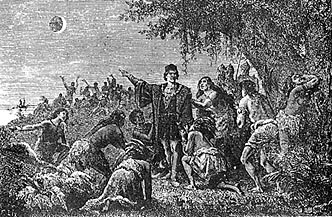

In the past 200 years, a

recurring theme in European eclipse stories involves western "scientific"

man taking advantage of the "superstitious" fear inspired

by eclipses to manipulate indigenous peoples. In one of the earliest

examples of this recurring story, Christopher Columbus, on his voyage

attempting to discover a western passage to the Indies, is stranded

in Jamaica, where he and his crew have stopped to gather supplies.

The local people are unwilling to provide the food and supplies

Columbus demands, and his crew is growing hungry and restless.

Stuck in this

awkward position, Columbus (it is said) hits on an ingenious solution:

from his astrological charts, he knows that a total lunar eclipse

will happen in a few days. When the day arrives, he gathers the

local people, tells them that he is very angry with them for withholding

supplies, and that he will show his wrath by causing the moon to

disappear. As if on cue, the moon begins to fade away behind the

shadow of the earth. The local people are struck with terror, and

they offer Columbus whatever he wishes, if only he will return the

moon to its place in the sky. Columbus relents, the moon reappears

in a few minutes, and Columbus and his crew are lavishly resupplied

and sent on their way by the grateful Jamaicans.

Though this

story may well be apocryphal, it provided the model for literary

eclipses for years to come. Mark Twain, in his book

A Connecticut

Yankee in King Arthur's Court

, has his main character, Hank

Morgan, use a similar gambit. Morgan is about to be burned at the

stake, so he "predicts" a solar eclipse he knows will

occur, claiming power over the sun, and offering to return the sun

to the sky in return for his freedom. "The rim of black spread

slowly into the sun's disk. . . . The multitude groaned with horror

to feel the cold uncanny night breezes . . . and see the stars come

out. . . ." Morgan is set free, and held in extreme awe for

his "wizardry."

|