|

|

|

|||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||

|

There are some good reasons to put a tree through all this injury (besides getting it to grow three different fruits). Consider orange trees: the roots of the tree that produces the sweet orange that we know and love can take up a virus that effects the growth of tree bark. The roots of the less-loved sour orange, however, won’t accept this virus. So by grafting sweet orange buds onto sour orange trees, growers in places like Texas protect their crop from disease. Grafting can make trees resistant to a variety of factors, including cold, drought, and microbes. A second reason to graft is that some tree families, such as citrus, don’t reproduce reliably. Oranges, for example, are either seedless, or are hybrids that may produce a tree that is somewhat different from its parent. Grafting gives growers a simple way to reproduce fruit trees without having to rely on seeds.

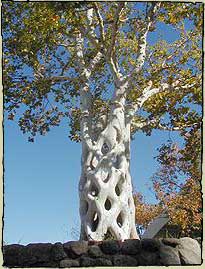

Ancient farmers and gardeners probably got the idea for grafting from nature itself. Young trees that sprout close together may graft as they grow up. Occasionally the branch of one tree will grow into the crook of another, and the pressure will injure the bark enough to allow the trees to graft. The creeping fig tree will graft its own branches in a tangle around another tree it uses for support. Other plants, such as rubber trees, are known to graft with each other at the roots. There are records of gardeners grafting in China and Mesopotamia as early as 2000 BC. Grafting was common in ancient Greece. In Renaissance England, grafters began making tree sculptures, and some artists and horticulturists continue the tradition today. For pictures of some fanciful grafts, check out the Circus Trees at Bonfante Gardens in Gilroy, CA: http://www.bonfantegardens.com/trees/trees.html http://www.arborsmith.com/treecircus.html

|

||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||

|

|

|

|

| © Exploratorium |