The SERENDIP project

The SERENDIP project has been using the Arecibo Radio Telescope

for the past 5 1/2 years listening to the sky with the long 430 MHz line

feed. They do not require telescope time of their own. SERENDIP just eavesdrops

on whatever the telescope happens to be looking at for other astronomers.

This is called a "piggyback" observation. Using this method, the

SERENDIP team has observed over 93% of the sky visible from Arecibo.

|

Maybe a little

SERENDIP

history

is in order here. SERENDIP started operation 18 years ago, in

1979, at the Hat Creek Observatory in Northern California near Lassen National

Park. The instrument used (now called SERENDIP I) was able to analyze 100

channels simultaneously. As advances in electronics took place, SERENDIP

II was developed and piggybacked onto the 300-foot-diameter radio telescope

at Green Bank, West Virginia. This newer instrument could analyze 65,000

channels simultaneously. In 1992 SERENDIP III was built and first used on

the Arecibo telescope. It could analyze over 4 million channels at once!

Now, the latest incarnation of SERENDIP, called (as you've probably guessed)

SERENDIP IV, has just started operation ar Arecibo Observatory. Rather than

looking at the sky around a frequency of 430 MHz like SERENDIP III, SERENDIP

IV will look at the sky at a higher frequency -- around 1420 MHz.

|

|

The Hat Creek Observatory in Northern California hosted the first SERENDIP

instrument in 1979. SERENDIP I analyzed 100 channels. The current instrument,

SERENDIP IV, analyzes 168 million channels at the same time.

|

|

|

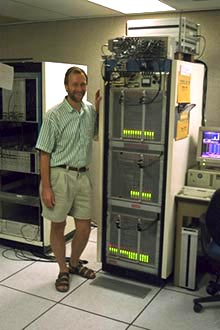

Principle Investigator Dan Werthimer with SERENDIP IV instrumentation, which

he designed and built.

|

|

The SERENDIP IV instrument can analyze 168 million channels

simultaneously! The frequencies around 1420 MHz are especially interesting

to look at because of their proximity to the "water hole." Also,

because of the importance of this part of the spectrum to radio astronomy,

by international agreement no one is allowed to produce any broadcasts between

1420 MHz and 1427 MHz. Because of this ban, it's an especially quiet part

of the spectrum. Let's take a closer look at what this means.

What exactly is SERENDIP looking for? As mentioned previously,

the most efficient way for an alien race to get noticed would be to concentrate

all the radio energy in a very narrow frequency signal. If your radio receiver

is "sloppy" and can only look at broad ranges of frequencies,

the narrow signal will get swamped by all the unwanted signals around it

-- even if that signal is very strong.

|

|

Imagine a person with a loud whistle in a huge noisy crowd. The whistle

has a very specific frequency or pitch. If you were just using your ears,

which pick up a wide range of pitches, the noise from the crowd would mask

out the whistle. On the other hand, what if your ears were tuned to listen

only for the pitch of the whistle? You wouldn't hear much of the crowd noise

because most of it wouldn't occur at the pitch you are "tuned"

to. But the whistle would come through loud and clear. In the same way,

the SERENDIP instrument listens in many precisely tuned channels (or frequencies)

for signals that are significantly "above the noise." SERENDIP

IV can listen to 168 million very narrow channels, each only 0.6 Hz wide.

You can quickly figure out by multiplying that SERENDIP IV can listen to

a range of frequencies 100 MHz wide! This means that SERENDIP IV will be

listening to a broad symphony at 1420 MHz plus and minus 50 MHz. And it

does this amazing analysis in only 1.7 seconds! This means that SERENDIP

IV can continuously monitor all of its channels as the telescope slowly

sweeps across the sky (Actually the sky slowly sweeps by the telescope).

|

|