|

How

to Melt a Glacier

|

|

by

Mary Miller

January

4, 2002

The

first thing you notice when you fly into the Lake Hoare field

camp in the Dry Valleys is the Canada Glacier. It’s like

a living, breathing presence, a wall of steep white ice atop

a lake the color of a blue tourmaline gemstone. When we hop

out of the helicopter after a twenty-minute ride from McMurdo

Station, I’d like to gawk at the glacier and the incredible

landscape of the Dry Valleys, but there’s work to be

done first.

After

we unload gear from the helicopter and wave goodbye to our

pilot, we get a quick orientation of the area by camp manager

Rae Spain. Rae has been working out in the Dry Valleys for

four years (she’s one of the pioneering women of the

Antarctic program and has spent twenty seasons on the continent),

and she outlines the camp rules for us. We are to leave no

trace of our presence here, except for footprints.

Everything

brought into the valley must be brought back out, including

all cooking and washing water and human urine and solid waste,

all of which is collected in barrels and flown back to McMurdo

for disposal. We also can’t take any souvenir rocks home

with us, which is a tough rule because the rocks here are

so beautiful and unique. We must content ourselves with taking

pictures instead.

The

reason for this environmental code of ethics is that this

unique and starkly beautiful place contains a very delicate

ecosystem. The Dry Valleys is a study site for intensive environmental

research, one of twenty-four Long Term Ecological Research

(LTER) projects in the United States. This site is particularly

important because it represents the only polar desert ecosystem

being studied and has been largely untouched by human presence.

|

|

|

|

|

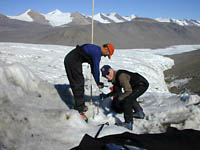

Paul

drills a hole that will help monitor the mass of the glacier.

Click

to enlarge

.

|

|

|

|

|

|

After

we get a lay of the land and have some lunch, geologist Andrew

Fountain takes me on a walking lesson in glaciology. Andrew,

a professor from Portland State University, has been studying

the Canada Glacier at Lake Hoare and other glaciers in the

Dry Valleys since 1993. As one of the project scientists for

LTER, it’s Andrew’s job to understand the role of

glaciers in the Dry Valleys ecosystem. In the coldest, driest

desert on earth, glaciers are the only source of water to

the lakes and soils here. With water comes life: This delicate

ecosystem is built upon single-celled microbes and algae,

which in turn support larger life forms such as nematode worms,

rotifers, and tardigrades.

Even

the tops of the glaciers provide a refuge for life. As soil

is blown across the valley floor, it collects on the glacier,

creating little pools of dirt and water called cryoconites.

These little pools harbor their own complete ecosystems of

microbes and invertebrates, some of which can live there for

years without making it to the valley floor. Such are the

extreme conditions for life in an ecosystem that has been

compared to Mars.

|