“.

. . not aware of the details of the results presented there when we devised

our structure.”

This

sentence marks what many consider to be an inexcusable failure to give

proper credit to Rosalind Franklin, a King’s College scientist.

Watson and Crick are saying here that they “were not aware of”

Franklin’s unpublished data, yet Watson later admits in his book

The Double Helix

that these data were critical in solving the

problem. Watson and Crick knew these data would be published in the same

April 25 issue of

Nature,

but they did not formally acknowledge

her in their paper.

What

exactly were these data, and how did Watson and Crick gain access to them?

While they were busy building their models, Franklin was at work on the

DNA puzzle using X-ray crystallography, which involved taking X-ray photographs

of DNA samples to infer their structure. By late February 1953, her analysis

of these photos brought her close to the correct DNA model.

What

exactly were these data, and how did Watson and Crick gain access to them?

While they were busy building their models, Franklin was at work on the

DNA puzzle using X-ray crystallography, which involved taking X-ray photographs

of DNA samples to infer their structure. By late February 1953, her analysis

of these photos brought her close to the correct DNA model.

But Franklin was frustrated with an inhospitable environment at King’s, one that pitted her against her colleagues. And in an institution that barred women from the dining room and other social venues, she was denied access to the informal discourse that is essential to any scientist’s work. Seeing no chance for a tolerable professional life at King’s, Franklin decided to take another job. As she was preparing to leave, she turned her X-ray photographs over to her colleague Maurice Wilkins (a longtime friend of Crick).

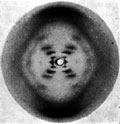

Then, in perhaps the most pivotal moment in the search for DNA’s structure, Wilkins showed Watson one of Franklin’s photographs without Franklin’s permission. As Watson recalled, “The instant I saw the picture my mouth fell open and my pulse began to race.” To Watson, the cross-shaped pattern of spots in the photo meant that DNA had to be a double helix.

Was it unethical for Wilkins to reveal the photographs? Should Watson and Crick have recognized Franklin for her contribution to this paper? Why didn’t they? Would Watson and Crick have been able to make their discovery without Franklin’s data? For decades, scientists and historians have wrestled over these issues.

To read more about

Rosalind Franklin and her history with Wilkins, Watson, and Crick, see

the following:

“Light on a Dark Lady” by Anne Piper, a lifelong friend of

Franklin’s

URL:

http://www.physics.ucla.edu/

~cwp/articles/franklin/piper.html

“The Double Helix and the Wronged Heroine,” an essay on

Nature’s

“Double Helix: 50 years of DNA” Web site

URL:

http://www.nature.com/cgi-taf/

DynaPage.taf?file=/nature/journal/

v421/n6921/full/nature01399_fs.html

A review of Brenda Maddox’s recent book,

Rosalind Franklin:

The Dark Lady of DNA

in

The Guardian

(UK)

URL:

http://books.guardian.co.uk/

whitbread2002/story/

0,12605,842764,00.html

© exploratorium