February

16, 2001

The Search to Understand Dyslexia

by Judith Brand

Developmental

dyslexia, a reading disorder affecting from 5 percent to 15 percent

of the population, can cast intelligent children into the category of

"poor readers." Yet with alternative methods of instruction,

dyslexic children can become competent readers and successful students.

In order

to effectively treat dyslexic children--that is, to design optimal

educational interventions--scientists are attempting to understand

the neurobiological foundations of the disorder. In the AAAS symposium

"Brain Mechanisms of Reading and Dyslexia," researchers

discussed what's known about dyslexia and the tools they're using

to get additional information.

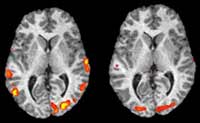

Perhaps

the most promising technique for studying dyslexia is functional magnetic

resonance imaging (fMRI). This is a noninvasive procedure that lets

the researcher see the brain in action. Interestingly, dyslexics and

nondyslexics often use different areas of their brains to deal with

the same reading task. "Before" and "after" fMRIs

of children who participate in reading intervention programs can reveal

physiological changes that

underlie improvements in the children's reading behavior. This knowledge

should lead to a better understanding of the causes of dyslexia, and

will help scientists and educators design more effective interventions.

|

These

functional magnetic resonance imaging (fMRI) images show the brain

of a nondyslexic person (left) and a dyslexic person (right).

The colored areas show the parts of the brains that are active,

or functioning, during the performance of a specific task. Although

both individuals are performing the same task, different regions

of their brains are active. This type of information can be used

to design better educational intervention techniques for people

with dyslexia. (Images courtesy of Guinevere Eden.)

|

Tips

for Parents

After the symposium, I asked two of the scientists what message they

might have for parents of young children. Dr. Frank Wood, of Wake

Forest University School of Medicine-- Bowman Gray, said that early

intervention can be extremely beneficial. Unfortunately, children

often aren't evaluated until it's apparent that they have a serious

reading problem. In Dr. Wood's opinion, it would be ideal to screen

all children, except those already reading fluently, by about January

of the first grade. If a child seems to have problems learning to

read by that time, parents might want to talk with the child's teacher

and possibly seek an evaluation for dyslexia through the school.

Researcher

Guinevere Eden from the Laboratory of Brain Function and Behavior

at Georgetown University Medical Center in Washington, D.C. (Photo

courtesy of Guinevere Eden.)

|

Dr.

Guinevere Eden, from Georgetown University Medical Center, noted that

dyslexic children have problems segmenting and manipulating the sounds

that make up words--skills that are necessary for reading proficiently.

Strengthening these skills will make any preschooler, dyslexic or

not, more "reading ready." Here are some games Dr. Eden

suggests parents might play with their kids to improve these skills:

"I've

always heard that dyslexia is characterized by the reversal of letters:

'b' for 'd,' and so on," an audience member asked. "What's

the story?"

The

answer may be both surprising and reassuring. According to Dr. Eden,

reversing letters is often just a sign that a child is a beginning

reader.

<<

Back to Dispatches