Girls of the Summer

Baseball is a game of history. It's almost impossible to listen to a game on the radio without being reminded of a record set 37 years ago, or a player whose deeds have never been equaled, whose name is remembered long after he's gone.

He. Most of the names and deeds and records in baseball have been set by men. It's largely considered a man's game. But what if you take a closer look at that history?

The first team of professional baseball players, the Cincinnati Red Stockings, took the field in 1869. They were all male -- the first boys of summer. The first girls of summer, women who were paid to play baseball, competed in their first game in 1875.

In the 1870s, an American woman could not vote. She could not own property in her own name after marriage. But she could play ball -- as well as it could be played in an outfit that weighed as much as 30 pounds and included a floor-length skirt, underskirts, a long-sleeved, high-necked blouse, and high-button shoes.

The Bloomer Girls

Amelia Bloomer designed and wore the loose-fitting, Turkish-style trousers that carried her name, and made sports more practical for women athletes. In the 1890s, scores of "Bloomer Girls" baseball teams were formed all over the country. (Eventually, many of them would abandon bloomers in favor of standard baseball uniforms.)

There was no league. Bloomer Girls teams rarely played each other, but "barnstormed" across America, challenging local town, semi-pro, and minor league men's teams to an afternoon on the diamond. And Bloomer Girls frequently won, playing good, solid competitive hardball. The teams were integrated when it came to gender; although most of the players were women, each roster had at least one male player. Future St. Louis superstar Rogers Hornsby got his start on a Bloomer Girls team.

The Bloomer Girls era lasted from the 1890s until 1934. Hundreds of teams -- All Star Ranger Girls, Philadelphia Bobbies, New York Bloomer Girls, Baltimore Black Sox Colored Girls -- offered employment, travel, and adventure for young women who could hit, field, slide, or catch.

The Bloomer Girls teams dwindled as more and more minor league teams -- farm clubs -- were formed to provide experience for young men on their climb up to the majors. A few women like Jackie Mitchell were signed, briefly, to minor league contracts, but they were exceptions.

Although women had been playing pro ball on Bloomer Girls teams for more than forty years, in the 1930s public opinion was that they had inferior abilities when it came to sports. Women's professional baseball disappeared when the last of the Bloomer Girls teams disbanded in 1934.

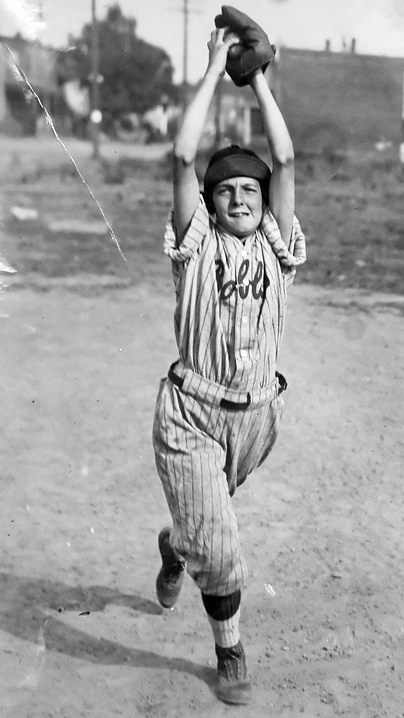

Photo courtesy Edith Houghton

Edith Houghton

Born 1912

Catcher

- Philadelphia Bobbies 1922-25

- New York Bloomer Girls 1925-31

- Hollywood Girls 1931

- Philadelphia Phillies (scout) 1946-52

Edith Houghton was only ten years old when she joined the Philadelphia Bobbies, a factory team made up of women, all of whom bobbed their hair. "The Kid" was so small that she had to tighten her cap with a safety pin and use a pen knife to punch new holes in the belt of her uniform pants. But Philadelphia sports reporters consistently praised both her hitting and fielding--at one time or another she played every position on the field.

In 1925, the Bobbies toured Japan, playing men's college teams for $800 a game. As a team they were less than spectacular, but the Japanese press had only good things to say about Edith.

When they returned home, Edith left the Bobbies to play for a number of women¹s teams, including Margaret Nabel's New York Bloomer Girls. She played one season for the Hollywood Girls, making $35 a week playing men¹s minor league teams.

In the mid-1930s, baseball opportunities for women disappeared with the demise of the Bloomer Girls teams, and Edith turned, reluctantly, to softball, playing for the Roverettes in Madison Square Garden. When World War II broke out, she enlisted in the Navy's women's auxiliary, the WAVES, and played on their baseball team as well.

After the war, Edith wrote to Bob Carpenter, owner of the Philadelphia Phillies, asking for a job as a scout. Carpenter looked through her scrapbook and decided to give her a chance, making her the first female scout in the major leagues. Edith scouted for the Phillies for six years before being called up by the Navy during the Korean War.

Edith Houghton eventually retired to Florida, where baseball -- at least watching spring training for the Phillies and the White Sox -- remains a big part of her life.

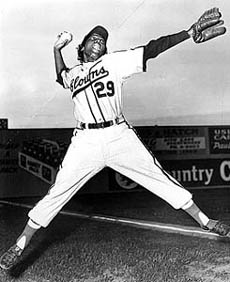

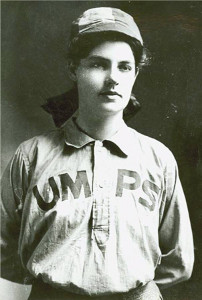

Photo courtesy Baseball Hall of Fame, Cooperstown, NY

In a barnstorming game, Lizzie once got a hit off the legendary pitcher, Satchel Paige. After the game, a reported asked negro league catcher Josh Gibson if Paige had really thrown his best pitch at Lizzie. Gibson said that Paige gave that pitch everything he had -- no way he wanted to be charged with a hit by a woman.

Lizzie Murphy

1894-1964

First Base

- Boston All-Stars 1918-1935

- American League All-Star Game 1922

- National League All-Star Game 1928

In her prime, Lizzie Murphy, also known as "Spike," was billed as the Queen of Baseball, the best woman player in the country. She started her career at age 15, playing for amateur teams around her hometown of Warren, Rhode Island, before signing with the Providence Independents. From there she moved up the baseball ladder to a nationally known semi-pro team, Ed Carr's All-Stars of Boston (often called the Boston All-Stars).

The team played more than 100 games a summer, barnstorming all over New England and Canada. Lizzie wore the regulation uniform of the day: a peaked cap, a wool shirt, baggy pants, and thick stockings with stirrups. Unlike the men's uniforms, however, Lizzie's had her name--LIZZIE MURPHY--stitched across both the front and the back, so that the crowd would know that the player at first base was the woman they'd come to see.

The team's official stationery featured a picture of Lizzie, which some members of the press thought was exploiting the young woman. Owner Carr replied, "She swells attendance, and she's worth every cent I pay her. But most important, she produces the goods. She's a real player and a good fellow." Lizzie herself took advantage of the "novelty" of her gender, and supplemented her income selling postcards of herself between innings, sometimes making as much as $50 per game.

In 1922, the Boston Red Sox sponsored a charity game against a combination of New England and American League All-Stars. Lizzie was chosen to play first base, becoming the first woman to play for a major league team in an exhibition game. In 1928, she played in the National League All-Star game, becoming the first person--of any gender--to play for All-Star teams in each league. (She also played a game in the Negro League, covering first base for the Cleveland Colored Giants.)

During the 1922 All-Star game, the team's third baseman decided to really put Lizzie to the test. The Sox batsman hit a hard grounder to third, and the third baseman fielded it cleanly -- and held it. When the runner was just a few steps away from first, he gunned it across the diamond as hard as he could. Lizzie caught it, and the runner was out. The third baseman shook his head, walked over to the shortstop, and said, "She'll do."

After seventeen years of playing professional baseball, Lizzie Murphy retired in 1935.

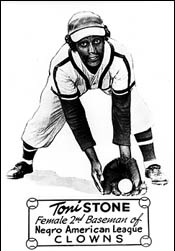

Photo courtesy The Buck O'Neil Collection, Negro Leagues Baseball Museum

Toni Stone (Marcenia Lyle Alberga)

1921-1996

Second Base

- San Francisco Sea Lions 1949

- New Orleans Creoles 1949-1952

- Indianapolis Clowns 1953

- Kansas City Monarchs 1954

Toni Stone may be one of the best ballplayers that you've never heard of.

As a teenager she played with the local boys' teams, in St. Paul, Minnesota. During World War II she moved to San Francisco, playing first with an American Legion team, and then with the San Francisco Sea Lions, a black, semi-pro barnstorming team--she drove in two runs in her first at-bat.

She didn't feel that the owner was paying her what they'd originally agreed on, so when the team played in New Orleans, she jumped ship and joined the Black Pelicans. From there she went to the New Orleans Creoles, part of the Negro League minors, where she made $300 a month in 1949. The local press reported that she made several unassisted double plays, and batted .265. (Although the All American Girls Baseball League was active at the time, Toni Stone was not eligible to play. The AAGBL was a "whites only" league, so Toni played on otherwise all-male black teams.)

In 1953, Syd Pollack, owner of the Indianapolis Clowns, signed Toni to play second base, a position that had been recently vacated when Hank Aaron was signed by the Boston (soon to be Milwaukee) Braves. Toni became the first woman to play in the Negro Leagues.

The Clowns had begun as a gimmick team, much like the Harlem Globetrotters, known as much for their showmanship as their playing. But by the '50s they had toned down their antics and were playing straight baseball. Although Pollack claimed he signed Toni Stone for her skill as a player, not as a publicity stunt, having her on the team didn't hurt revenues, which had been declining steadily since Jackie Robinson broke the color barrier in the majors, and many young black players left the Negro Leagues.

Stone recalls that most of the men shunned her and gave her a hard time because she was a woman. She reflected that, "They didn't mean any harm, and in their way they liked me. Just that I wasn't supposed to be there. They'd tell me to go home and fix my husband some biscuits, or any damn thing. Just get the hell away from here."

The team publicized Toni Stone in interviews, on posters, and on the cover of the Clowns' program. And she got to play baseball, appearing in 50 games in 1953, and hitting .243. In 1954, Pollack sold her contract to the Kansas City Monarchs, an all-star team that had won several pennants in the "Colored World Series," and for whom Jackie Robinson and Satchel Paige had both played.

(When Stone left the Clowns, Pollack hired Connie Morgan to replace her at second base, and signed a female pitcher, Mamie "Peanut" Johnson, as well.)

She played the 1954 season for the Monarchs, but she could read the handwriting on the wall. The Negro Leagues were coming to an end, so she retired at the end of the season. She was inducted into the Women's Sports Hall of Fame in 1993. She is honored in two separate sections in the Baseball Hall of Fame in Cooperstown; the "Women in Baseball" exhibit, and the Negro Leagues section.

Toni Stone's most memorable baseball moment came when she played against the legendary Satchel Paige in 1953. "He was so good," she remembered, "That he'd ask batters where they wanted it, just so they'd have a chance. He'd ask, 'You want it high? You want it low? You want it right in the middle? Just say.' People still couldn't get a hit against him. So I get up there and he says, 'Hey, T, how do you like it?' And I said, 'It doesn't matter, just don't hurt me.' When he wound up--he had these big old feet--all you could see was his shoe. I stood there shaking, but I got a hit. Right out over second base. Happiest moment in my life."

Photo source unknown

Maud Nelson (Clementina Brida)

1881–1944

Third Base

- Western Bloomer Girls

- All-Star Ranger Girls

For over forty years, Maud Nelson was active in every facet of women's baseball. She was a pitcher, played third base, scouted, and owned or managed some of the finest women's teams to play in the early days. In 1908, one reporter wrote that she was "the greatest all-around female ball player in existence."

Maud was the starting pitcher for the barnstorming Boston Bloomer Girls in 1897. The team once won an amazing 28 games in 26 days, and a Eugene, Oregon, paper said, "The girls from Beantown put up a clean game and play like professionals, asking for no favors, but playing a hard, snappy game on its merits."

Maud was the star attraction for the team, and had to pitch every day, so as not to disappoint the fans. Often she would strike out the side for two or three innings, turn the ball over to the bullpen, then finish the game at third base, fielding grounders and rocketing bullets over to first base for another six innings.

When she was thirty, she became the owner-manager (with her husband, John Olson) of the Western Bloomer Girls. She scouted both male and female players, dealt with booking agents, handled contracts, and managed the day-to-day operations of the team. Her husband died in 1917; six years later she remarried, and with her new spouse, Costante Dellacqua, formed the All-Star Ranger Girls. The Ranger Girls would play until 1934.

Wherever she traveled, Maud recruited the cream of the local crop to play on her teams. Many of the best players in the early years of this century played either with or for her. For three generations of women, Maud Nelson offered the opportunity of a lifetime--the chance to play professional baseball.

Photo courtesy Dottie Stolze

Dottie Stolze

Born 1923

Shortstop

- Muskegeon Lassies

Dottie Stolze was playing softball on a women's team in Alameda, California, when former major leaguer Max Carey saw her and signed her to play with his AAGBL team--the Muskegeon Lassies. The season was already in progress; she was put in as the shortstop almost as soon as she arrived. But she distinguished herself in that first game by getting a triple.

Hampered by an elbow injury incurred in a car accident, she started having trouble making the long throws from short, and was moved to second base the next season. For most of her career, she generally played second base, but also served as a utility player for the Lassies, covering every position except pitcher at one time or another.

The Lassies drew over 9,000 visitors to many games in the 1947 season, when they were the league champions. Dottie's best year was 1948, when she batted .242, had 62 runs, and stole 67 bases.

She played seven seasons in the AAGBL, retiring in 1952. She returned to college to get her degree, and went on to teach physical education and coach girls' softball teams for many years.

Photo courtesy The Northern Indiana Historical Society

Rose Gacioch

Born 1915

Right Field

- All-Star Ranger Girls 1934

- South Bend Blue Sox 1944

- Rockford Peaches 1945-1954

Rose Gacioch was 16 years old when her mother died. She lied about her age, said she was 18, and got a job in a corrugating plant in Wheeling, West Virginia. She also joined the Little Cardinals, the boy's baseball team in town. One afternoon in 1934, the president of the corrugating company came to a Little Cardinals game. He knew Maud Nelson, the manager of the All-Star Ranger Girls, and asked Maud if she'd swing through Wheeling on her next tour, and give this kid a tryout.

The kid did good. Maud Nelson signed Rose for the Rangers, where she alternated between the outfield and pitching. But 1934 was the last year that the "Bloomer Girls" teams would play. Companies that had sponsored women's baseball were switching over to the less expensive game of softball--a game that relied mainly on one outstanding player, the pitcher.

So Rose, like most other women players, switched to softball, barnstorming around the Midwest on weekends for as much as $50 for two days' play. She was working in a factory during World War II when she read about the new women's baseball league, the All-American Girls Baseball League, being formed.

"I'm going to be on that team," she announced one day at lunch. Her fellow workers laughed. Rose was 28 years old, much too old to play baseball. But another co-worker said that his daughter was a chaperone for the South Bend Blue Sox, and he'd ask her to come and look Rose up.

She made the cut and played for the Blue Sox in the 1944 season under manager Bert Niehoff, the same man who had sent Jackie Mitchell to the mound to face Babe Ruth a decade earlier.

In 1945, Rose was one of the ten players on the Blue Sox Niehoff asked to have protected from being traded at a league meeting in Chicago. But the president of the ball club, a Mr. Livengood, decided that Gacioch's poor English made her a liability for the team, not the ladylike image he was seeking. And so he traded her to the Rockford Peaches for the 1945 season.

It was a bad move on Livengood's part. As a member of the Rockford team, Rose lead the league in 1946 with nine triples, and batted .262. Peaches Manager Bill Allington moved her from the outfield to the pitcher's mound in 1948; her record was 14-5 that season. Her best year with the Peaches was 1951, when she went 20-7, becoming the league's only 20-game winner. She pitched a no-hitter in 1953, and was voted to the AAGBL All-Star team in 1952, '53, and '54.

Rose Gacioch stayed with the Peaches until the league disbanded in 1954, and she retired from baseball at the age of 39.

Photo courtesy Laura Wulf

Kim Braatz-Voisard

Born 1969

Center Field

- Colorado Silver Bullets 1994-1997

In 1994, the Colorado Silver Bullets were formed, the first women's professional baseball team since the All-American Girls Baseball League disbanded in 1954. They were a touring team, traveling around the country from May to September, playing men's college, amateur, semi-pro, and professional minor league teams.

Like most of the women on the team, Kim Braatz-Voisard played softball in high school, because she was not allowed to play on the boys' baseball team. At the University of New Mexico, Kim continued to play softball, occasionally taking batting practice with the baseball team.

According to Kim, the biggest obstacle the women of the Silver Bullets had to overcome was making the change from the underhand pitch (and larger ball) of softball. It takes some time to learn to read an overhand pitch. But as they got more familiar with the style and rhythms of baseball, the team's record improved from a dismal 6-44 in their first season to a winning 23-22 in 1997.

Braatz said the highlight of her baseball career was hitting the team's first home run against the Cape Cod League All-Stars in 1996.

At the end of the 1997 season, the team's sponsor, Coors Light, announced it was ending its support, having invested more than $8 million over the previous four years. Reportedly, Coors was also concerned that, at a time when there's an upsurge in women's sports, Coors might be viewed as a women's beer.

Photo courtesy The Northern Indiana Historical Society

Sophie Kurys

Born 1925

Left Field

- Racine Belles 1943-1950

In 1943, Sophie Kurys signed with the Racine Belles of the All-American Girls Baseball League. That first season, the eighteen-year-old, known as "The Flint Flash," was the team's left fielder and stole forty-four bases. The next season, she moved to second base, where she played in 116 games and stole a league-leading 166 bases (out of 172 tries). But she was just warming up.

In 1946, she was the league's Player of the Year, for a number of amazing feats. In 113 games, she had 112 hits, scored a league-leading 117 runs, and batted .286, the second-highest average in the league that year, with a phenomenal .973 fielding record at second base.

She also stole 201 bases (out of 203 tries). That's a record unequaled anywhere in professional baseball. Lou Brock held the men's record of 118 stolen bases in a season, until Rickey Henderson broke it in 1982, stealing 130 that year.

Sophie's feats didn't go unnoticed in the wider world of baseball. The 1947 yearbook, Major League Baseball Facts, Figures, and Official Rules, featured Stan Musial on its front cover, and Sophie Kurys on the back cover.

And she set that stealing record in a skirt. That's not an insignificant detail. The uniforms for the women who played in the AAGBL were skirts because the management wanted to show the world that these were extremely feminine women. No tomboys, was the official line. But that meant that when a runner like Kurys slid into second, she did it with bare legs.

Sliding across the hard-packed dirt of the infield resulted in huge bruises and multiple "strawberries"-- broken skin that often bled through the players' uniforms. Kurys said, "The year I set the record, my chaperone made this donut affair so the wound wouldn't leak onto my clothes, because if it did, it would be torture to try to get the clothes off. . . . I had strawberries on strawberries. Sometimes now, when I first get up in the morning, I have problems with my thighs."

Despite that, Kurys stole a league record 1,114 bases in the eight seasons she played for the AAGBL. (Only Rickey Henderson, who has stolen 1279 bases in 20 seasons of play, has a higher career total.)

Can you compare the single-season base-stealing records of Sophie Kurys and Rickey Henderson? In their respective record seasons, Henderson stole 65% as many bases as Kurys.

But in 1946, the AAGBL's base paths were 20% shorter -- 72 feet, compared to the major league's 90 feet -- and the ball used was slightly larger. (By 1954, the last year of the AAGBL, the base path lengths and ball size were the same as those in the majors.)

So, according to Dr. Robert K. Adair, a physics professor at Yale, an AAGBL runner like Kurys had a theoretical .04 second advantage over the pitcher-catcher battery. Henderson and other major league runners have a .15-second disadvantage.

But Dr. Adair stresses that those microsecond numbers reflect perfect conditions. The athlete would have to have Olympic-quality speed and an uncanny ability to judge the right moment to steal in order to gain that .04 second advantage.

There are too many variables to really make accurate comparisons: the condition of the field, the speeds of the individual pitchers, the speed and accuracy of the catchers, the skills of the people playing second base. Each of those has an affect on the statistics -- whether the competition is real or projected.

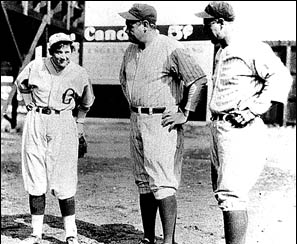

Photo courtesy The Chattanooga Regional Historical Museum

Jackie Mitchell

1914-1987

Pitcher

- Chattanooga Lookouts 1931

In the spring of 1931, Joe Engel, owner of the Southern Association's AA Chattanooga Lookouts, signed 17-year-old pitcher Jackie Mitchell. The Chattanooga papers were full of stories about the first woman to ever play in the minor leagues. (Jackie Mitchell was actually the second woman to sign a minor-league contract. In 1898, Lizzie Arlington played one game, pitching for Reading (PA) against Allentown.)

On April 2 of that year, the New York Yankees stopped in Chattanooga for an exhibition game, on their way home from spring training down south. A crowd of 4,000 came to watch, including scores of reporters, wire services, and even a newsreel camera.

Manager Bert Niehoff started the game with Clyde Barfoot, but after Barfoot gave up a double and a single, the manager signaled for Jackie Mitchell. The rookie southpaw took the mound wearing a baggy white uniform that had been custom-made by the Spalding Company. The first batter she faced was Babe Ruth.

Jackie only had one pitch, a wicked, dropping curve ball. Ruth took ball one, and then swung at -- and missed -- the next two pitches. Jackie's fourth pitch caught the corner of the plate, the umpire called it a strike, and Babe Ruth "kicked the dirt, called the umpire a few dirty names, gave his bat a wild heave, and stomped out to the Yank's dugout."

The next batter was Lou Gehrig. He stepped up to the plate and swung at the first sinker -- strike one! He swung twice more, hitting nothing but air. Jackie Mitchell had fanned the "Sultan of Swat" AND the "Iron Horse," back-to-back.

After a standing ovation that lasted several minutes, Jackie pitched to Tony Lazzari, who drew a walk. At that point, Niehoff pulled her and put Barfoot back in. The Yankees won the game 14-4.

A few days after the exhibition game, Baseball Commissioner Kenesaw Mountain Landis voided Jackie Mitchell's contract, claiming that baseball was "too strenuous" for a woman.

Crushed and disappointed, Jackie began barnstorming, traveling across the country pitching in exhibition games. In 1933, when she was 19, she signed on with the House of David, a men's team famous for their very long hair and long beards. She traveled with them until 1937, but eventually got tired of the sideshow aspects of barnstorming -- like playing an inning while riding a donkey.

At the age of 23, she retired and went to work in her father's optometry office, although she continued to play with local teams from time to time.

The Press Had Widely Varying Opinions About Women Pitchers

"She uses an odd, side-armed delivery, and puts both speed and curve on the ball. Her greatest asset, however, is control. She can place the ball where she pleases, and her knack at guessing the weakness of a batter is uncanny .... She doesn't hope to enter the big show this season, but she believes that with careful training she may soon be the first woman to pitch in the big leagues." The Chattanooga News, March 31, 1931

"The Yankees will meet a club here that has a girl pitcher named Jackie Mitchell, who has a swell change of pace and swings a mean lipstick. I suppose that in the next town the Yankees enter they will find a squad that has a female impersonator in left field, a sword swallower at short, and a trained seal behind the plate. Times in the South are not only tough but silly." The New York Daily News, April 2, 1931

"I don't know what's going to happen if they begin to let women in baseball. Of course, they will never make good. Why? Because they are too delicate. It would kill them to play ball every day." Babe Ruth

"Cynics may contend that on the diamond as elsewhere it is place aux dames. Perhaps Miss Jackie hasn't quite enough on the ball yet to bewilder Ruth and Gehrig in a serious game. But there are no such sluggers in the Southern Association, and she may win laurels this season which cannot be ascribed to mere gallantry. The prospect grows gloomier for misogynists." The New York Times, April 4, 1931

Photo courtesy The Baseball Hall of Fame Library, Cooperstown, NY

Pam Postema

Born 1954

Umpire

- Minor leagues 1977-1988

- Major league spring training 1988-1989

- Hall of Fame Game (Yankees vs. Braves) 1988

Pam Postema followed in the footsteps of Bernice Gera [See the footnote about Gera below] and applied to the Al Somers Umpire School in Florida in 1976. After ignoring her original application, then rejecting her second one because the school didn't have proper facilities for women, Somers relented and accepted her into the school.

That season, 130 students were admitted. Thirty of them quit or were dismissed; Postema made it through, graduating high in her class. She spent three months looking for a job at the high school, college, or semi-pro levels, and was just about to give up when she got a letter offering her a job in the rookie Gulf Coast League.

She umpired there for two seasons, then spent two more with the Single-A Florida State League. After another two years at the AA level, she made it to the top of the minors, Triple-A baseball, with the Pacific Coast League.

Although many players were supportive and spoke highly of Postema's skill as an umpire, other men felt differently. At one game she arrived at home plate to find a frying pan, with a note telling her where she could go with it.

Pam umpired at the AAA level for six years, always considered a "prospect" for the majors, but never getting the call. In 1988 she was invited to umpire major league games during spring training, and later that year Commissioner Bart Giamatti asked her to officiate at the Hall of Fame Game between the Yankees and the Braves. Pam saw those two opportunities as hope for a major league contract.

But Giamatti died in 1989, and Pam Postema's hopes for a major league spot died with him. After 13 years umpiring in the minor leagues, the Triple-A alliance cancelled her contract in December of 1989. She filed a federal sex-discrimination lawsuit, declaring, "I believe I belong in the major leagues. If it weren't for the fact that I'm a woman, I would be there right now." The suit was settled out of court.

In 1992, Pam Postema published a book called "You've Got to Have Balls to Make it in This League."

Bernice Gera

In 1969, Bernice Gera (1932-1992) was the first woman to go through umpiring school and get a contract to work in the minor leagues. The day before she was going to umpire her first game, she received a letter from the president of the NAPBL (the minor league system), informing her that her contract had been rescinded. No reasons were given. Gera took the case to the New York State Human Rights Commission, which ruled in her favor. The NAPBL appealed, and the appellate court upheld the ruling in Gera's favor. The league appealed again, and was again rebuffed. A year later, without giving any reasons, the league gave Gera a contract and told her to report on June 23, 1972. She umpired a single game, and then resigned. "I was physically, mentally, and financially drained," she said. "It is hard to get used to having people spit at you and threaten your life."

Photo courtesy The South Dakota Amateur Baseball Hall of Fame

Amanda's brother, Hank Clement, eventually married and had six children, all of whom played baseball with Aunt Amanda at one time or another. Even when she was in her forties, Amanda threw so hard that her nephews had to stuff their gloves with sponges to keep their hands from stinging.

Amanda Clement

1888–1971

Umpire

Amanda Clement was the first woman ever paid to umpire a baseball game. In 1904, her family traveled from their home in South Dakota to Iowa to watch her brother Hank pitch in a semi-pro game. The first game of the afternoon was an amateur game, and the scheduled umpire hadn't shown up. Hank said that his 16-year-old sister was a pretty good ball player and could take the guy's place. The semi-pro teams were so impressed with her officiating that they hired her on the spot.

In those days, umpires stood behind the pitcher. Amanda tucked her long hair under her cap, and tucked a few extra baseballs into the waistband of her ankle-length blue skirt. Then she yelled, "Play ball!" and made all the calls at the plate, on the bases, and in the outfield.

She umpired semi-pro games for the next six years, working 50 games a summer, for pay of $15 to $25 per game. She became so well known that when there was an important game anywhere in the northern Midwest, she was the first umpire called.

Her umpiring pay put her through college--first at Yankton College, then the University of Nebraska, where she both umpired and played basketball and tennis. After she graduated, she taught high school physical education, taught at the University of Wyoming, and later became a social worker. She was inducted into the South Dakota Hall of Fame in 1964.

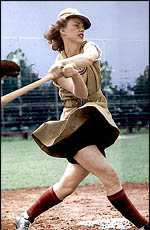

A League Of Their Own

There were professional softball teams for women, but that's a very different game -- shorter base paths, a larger ball, underhand pitching, no steals. In 1943, with many major league players off at war, Philip K. Wrigley organized the All-American Girls Softball League to entertain fans. The league's rules permitted stolen bases, but it was essentially softball.

For the first season anyway. In the twelve years that the league existed, it slowly evolved from softball to baseball-like softball, to baseball, eventually becoming the All-American Girls Baseball League (AAGBL). The base paths got longer from season to season, and the ball got smaller, so that by the last season, in 1954, the women were playing straight baseball. They played in skirts, but they played baseball.

Popularized in the movie A League of Their Own , the AAGBL teams played for twelve seasons. Over six hundred women played for Midwestern teams like the Rockford Peaches, the Muskegon Lassies, and the Racine Belles. According to the book Women at Play by Barbara Gregorich, "For those who actually saw them play, the women of the AAGBL changed forever the unquestioned concept that women cannot play baseball. For their managers, they played the national pastime as only professionals can . . . . They were equal to the game . . . more serious than the skirts they were required to wear, more intelligent than the various board directors who would not let them become managers."

The All-American Girls Baseball League played its last season in 1954. Television was bringing men's major league games into people's living rooms, and there just wasn't enough audience for the women's league to continue.

In June of 1952, shortstop Eleanor Engle signed a minor league contract with the AA Harrisburg Senators. George Trautman, head of the minor leagues, voided the contract two days later, declaring that "such travesties will not be tolerated." On June 23, 1952, organized baseball formally banned women from the minor leagues.

After the demise of the AAGBL, women who wanted to play professional ball had no choice but to play softball. There have been very few exceptions since.

Toni Stone, Connie Morgan, and Mamie "Peanuts" Johnson played on otherwise all-male teams in the Negro Leagues in the 1950s. A few plucky women showed up from year to year at tryouts for minor league teams, but were never offered contracts.

In 1994, exactly forty years after the AAGBL folded, the Colorado Silver Bullets opened the first of their four seasons. Again, there was no league, just a team of women who once again went barnstorming across the country, playing men's college, amateur, and semi-pro teams.

In 1998, Ila Borders, a pitcher for the Duluth Dukes, an independent minor league team, became the first woman to win a men's pro game, nailing down a 3-1 victory over the Sioux Falls Canaries. But she couldn't break the gender barrier that has kept major league baseball diamonds the exclusive playgrounds for the boys of summer, and she retired from baseball in 2000.