|

Continued from Page One

A vivid memory

of a traumatic event, right? Well, not exactly. Piaget goes on: "When

I was about fifteen, my parents received a letter from my former nurse

saying that she had been converted to the Salvation Army. She wanted to

confess her past faults, and in particular to return the watch she had

been given on this occasion. She had made up the whole story, faking the

scratches. I, therefore, must have heard, as a child, the account of this

story, which my parents believed, and projected it into my memory."

A vivid memory

of a traumatic event, right? Well, not exactly. Piaget goes on: "When

I was about fifteen, my parents received a letter from my former nurse

saying that she had been converted to the Salvation Army. She wanted to

confess her past faults, and in particular to return the watch she had

been given on this occasion. She had made up the whole story, faking the

scratches. I, therefore, must have heard, as a child, the account of this

story, which my parents believed, and projected it into my memory."

Piaget was remembering

something he'd been told about, but never experienced. Memory researcher

Elizabeth Loftus has experimented extensively in the laboratory with how

memories can be changed by things that you are told. Your memories are

vulnerable to what she calls "post-event information"--facts,

ideas, and suggestions that come along after the event has happened. You

can, unknowingly, integrate this information into your memory, modifying

what you believe you saw, you heard, you experienced. Over time, you can

integrate post-event information with information you gathered at the

time of the event in such a way that you can't tell which details came

from where, combining all this into one seamless memory.

Piaget was remembering

something he'd been told about, but never experienced. Memory researcher

Elizabeth Loftus has experimented extensively in the laboratory with how

memories can be changed by things that you are told. Your memories are

vulnerable to what she calls "post-event information"--facts,

ideas, and suggestions that come along after the event has happened. You

can, unknowingly, integrate this information into your memory, modifying

what you believe you saw, you heard, you experienced. Over time, you can

integrate post-event information with information you gathered at the

time of the event in such a way that you can't tell which details came

from where, combining all this into one seamless memory.

The information

that you integrate can come from something as subtle as a leading question.

In laboratory situations, Loftus has documented such memory modifications.

After showing a group of college students a film of an automobile accident,

she asked a number of questions about the event. Among other questions,

one group of students was asked, "About how fast were the cars going

when they hit each other?" Another group was asked, "About how

fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?" A third

group was not asked about the cars' speed.

The information

that you integrate can come from something as subtle as a leading question.

In laboratory situations, Loftus has documented such memory modifications.

After showing a group of college students a film of an automobile accident,

she asked a number of questions about the event. Among other questions,

one group of students was asked, "About how fast were the cars going

when they hit each other?" Another group was asked, "About how

fast were the cars going when they smashed into each other?" A third

group was not asked about the cars' speed.

The students who

were asked about the cars' speed when they "hit" estimated speeds

significantly lower than the students who were asked about the cars' speed

when they "smashed into" each other. A week later, Loftus asked

the students another series of questions about the accident, including

"Did you see any broken glass?" The film had shown no broken

glass, but the students who had been asked about the cars "smashing

into" each other were much more likely to remember broken glass--which

makes sense since an accident at a higher speed is more likely to result

in broken glass.

The students who

were asked about the cars' speed when they "hit" estimated speeds

significantly lower than the students who were asked about the cars' speed

when they "smashed into" each other. A week later, Loftus asked

the students another series of questions about the accident, including

"Did you see any broken glass?" The film had shown no broken

glass, but the students who had been asked about the cars "smashing

into" each other were much more likely to remember broken glass--which

makes sense since an accident at a higher speed is more likely to result

in broken glass.

With the same sort

of questioning, Loftus has led people to believe that they saw a yield

sign where they saw a stop sign, to remember a clean-shaven man as having

a mustache, to recall straight hair as curly.

With the same sort

of questioning, Loftus has led people to believe that they saw a yield

sign where they saw a stop sign, to remember a clean-shaven man as having

a mustache, to recall straight hair as curly.

Maybe that doesn't

seem like such a big deal to you. Sure, the details may be off, but the

basic memory itself is still correct. It's not as though it's a false

memory--like being a secret agent on Mars, say, or having someone try

to kidnap you from your pram.

Maybe that doesn't

seem like such a big deal to you. Sure, the details may be off, but the

basic memory itself is still correct. It's not as though it's a false

memory--like being a secret agent on Mars, say, or having someone try

to kidnap you from your pram.

|

|

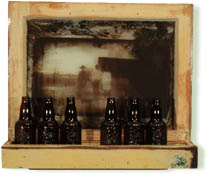

By

Mildred Howard. From the collection of Daniel Schacter.

|

|

But Loftus's research

doesn't stop there. Working with her students, she has created whole memories,

as detailed as Piaget's memory of the attempted kidnapping. One of her

students provided his fourteen-year-old brother, Chris, with one-paragraph

written descriptions of four childhood events, one of which was false.

(The false event was that Chris had been lost in a shopping mall when

he was five.) Over the next five days, Chris wrote about whatever details

he could remember from all four events, adding details to his "memories."

But Loftus's research

doesn't stop there. Working with her students, she has created whole memories,

as detailed as Piaget's memory of the attempted kidnapping. One of her

students provided his fourteen-year-old brother, Chris, with one-paragraph

written descriptions of four childhood events, one of which was false.

(The false event was that Chris had been lost in a shopping mall when

he was five.) Over the next five days, Chris wrote about whatever details

he could remember from all four events, adding details to his "memories."

A few weeks later,

Chris was asked to describe each event and rate the clarity of each memory

on a scale of one (not clear at all) to eleven (very, very clear). The

shopping mall memory got his second-highest rating, number eight. He could

describe being lost in detail.

A few weeks later,

Chris was asked to describe each event and rate the clarity of each memory

on a scale of one (not clear at all) to eleven (very, very clear). The

shopping mall memory got his second-highest rating, number eight. He could

describe being lost in detail.

Finally, Chris

was told that one of his memories was false. When asked which one he thought

it was, he chose one of the real memories. When told that the shopping

mall memory was fabricated, he had a hard time believing it.

Finally, Chris

was told that one of his memories was false. When asked which one he thought

it was, he chose one of the real memories. When told that the shopping

mall memory was fabricated, he had a hard time believing it.

Other researchers

have produced similar results. Dr. Stephen Ceci and his colleagues asked

preschool children about things that had happened to them and, in the

same conversation, about something that had never happened: for instance,

the time they got a finger caught in a mousetrap and had to go to the

hospital to get the trap off. Once a week, for ten weeks, the children

were asked to think hard about the events and try to imagine them. Finally,

the children were asked about the imaginary events.

Other researchers

have produced similar results. Dr. Stephen Ceci and his colleagues asked

preschool children about things that had happened to them and, in the

same conversation, about something that had never happened: for instance,

the time they got a finger caught in a mousetrap and had to go to the

hospital to get the trap off. Once a week, for ten weeks, the children

were asked to think hard about the events and try to imagine them. Finally,

the children were asked about the imaginary events.

More than half

the children remembered the made-up events, complete with details about

how the mousetrap got on their finger and what had happened at the hospital.

More than half

the children remembered the made-up events, complete with details about

how the mousetrap got on their finger and what had happened at the hospital.

|