|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|

||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

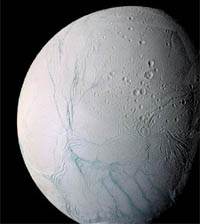

Cassini flybys of Saturn’s bright little moon Enceladus have revealed geysers spewing water vapor and ice crystals high above the moon’s south pole. It’s quite remarkable that this small moon, only 300 miles (less than 500 km) in diameter, is geologically active. But the real surprise is the probable source of the eruptions: pockets of liquid water close to the satellite’s surface. With the possibility of liquid water comes the question, could life arise? According to Dr. Carolyn Porco, head of the Cassini imaging team, “If we are right [that there is evidence of liquid water], we have significantly broadened the diversity of solar system environments where we might possibly have conditions suitable for living organisms.”

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

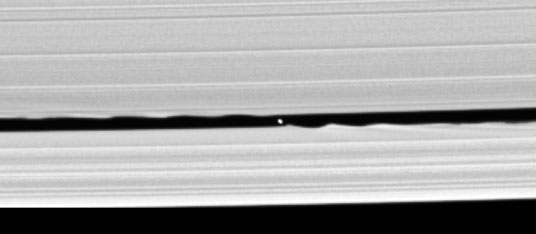

These moons have elongated, inclined orbits, which puts them in a class called irregular satellites . And all but one travel around Saturn in the opposite direction to Saturn’s rotation. Both the irregularity and the direction of their orbits indicate that they were captured by Saturn from their original paths around the sun. Under the current conditions of the solar system, it wouldn’t be possible for a planet to kidnap, say, a passing asteroid, so irregular satellites must have been captured long ago. Studying these moons will tell us about an earlier time, possibly a time shortly after the planets were formed. Moons Make WavesA new moon spotted by Cassini in May 2005 gratified scientists who had predicted its existence. The little moon, known as S/2005 S1 for now, was found hiding in the Keeler gap in Saturn’s A ring. The tip-off came when scientists noticed that the uneven edges of the Keeler gap were similar to those of the Encke gap, also in the A ring, which is home to the moon Pan. The wavy edges of the gaps indicate that the embedded moons have an effect on the material that makes up the rings.

The photo (above) of the Keeler gap provides a compelling lesson in orbital mechanics. The top of the image is closest to Saturn and the moon is moving leftward. The ring particles closer to Saturn (above the moon) orbit faster than the moon so that they carry the wavy perturbations ahead of the moon, to the left. The ring particles below the moon orbit slower than the moon and so the ripples stretch behind the moon to the right. An important property of the ripples is how fast they die out. Notice that they are larger near the moon and smaller farther away. The ring particles orbit in the vacuum of space so they move without friction in the classical earthbound sense. But something is causing the ripples to die out. Finding out the exact origin of the damping of the waves will help us understand the size distribution and density of particles that make up the rings and also how they interact with each other in the presence of Saturn’s gravity. Moons Receive New NamesThe first moons discovered by Cassini in the summer of 2004 have traded in their temporary appellations for more melodious mythological names. No longer plain S/2004 S1 and S/2004 S2, these tiny inner moons are now Methone and Pallene, named for two of seven sisters known as the Alkyonides. They orbit between two of Saturn’s major moons, Mimas and Enceladus.

A third moon, S2004 S5, is now called Polydeuces. In Greek mythology, Polydeuces (or Pollux) is the son of Zeus, which makes him the grandson of Cronus—who the Romans called Saturn. Polydeuces is interesting because it’s a Trojan moon, a moon that travels in the same orbit as a larger moon, either 60 degrees ahead of it or behind it. Polydeuces travels behind Dione, which has a second companion, Helene, that travels in front of it.

After a seven-year journey aboard the spaceship Cassini, Huygens separated from its mother ship on December 25 and coasted a million miles toward Titan. It reached its target exactly as planned, then spent two-and-a-half hours descending 700 miles through Titan’s atmosphere. Along the way, it sampled and analyzed gases in the atmosphere, recorded sounds, took images of Titan’s surface, and collected a wealth of other data.

A soft landing

Undamaged by the landing, Huygens survived on Titan for about five hours—far exceeding the “best case” expectations of thirty minutes—and was able to transmit about two hours of useful data.

Like the earth—only different

The main visual difference between Titan’s landscape and that of the earth is that there’s no vegetation or other sign of life. But there are major chemical differences as well. First of all, those rocks are likely to consist of water ice. With a surface temperature hovering at around -300°F (-180°C), rocks of water ice would be as hard as the silicate rocks on earth and would be in no danger of melting. The rocks show signs of weathering, however, and clouds over Titan indicate that the moon does experience weather. In place of the liquid water that rains onto the earth, though, it appears that Titan is showered with methane. At Titan’s temperatures, methane can exist as a solid, liquid, or gas, so it’s very probable that Titan has a “methane cycle” similar to the earth’s water cycle. The land in between the rocks in the image is like the soil Huygens landed on. It appears that it’s a granular water ice mixed with hydrocarbons and saturated with liquid methane. Heat generated by Huygens caused bursts of methane gas to rise from the soil, where the gas was detected by two of the Huygens instruments. Another feature of Titan’s soil is that there are dark spots, particularly in riverbeds and other low-lying areas. It seems that hydrocarbons from the atmosphere settle on the land but are washed off high surfaces by rain.

A young surface

We have, then, a place that shares many of earth’s geophysical and meteorological processes, but processes that work on entirely different substances and at temperatures that are so cold it’s hard to imagine them. Titan is nothing short of astonishing.- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Titan’s intriguing surface Although Titan has undoubtedly been bombarded by comets and asteroids during its history, Cassini did not find a cratered surface such as exists on our own moon. In fact, in the area surveyed by radar, approximately 1 percent of the surface, there were only slight variations in elevation. A strong possibility is that the surface of the moon is being fashioned by geologic processes that make it “young.” What the Cassini radar did see is that there’s considerable variation in the terrain. Basically, bright areas are interpreted as rough terrain and dark areas as smooth. But what makes up the smooth areas? Ice is likely, but liquid would have a smooth appearance as well. Whether or not lakes exist is still a major question. With a surface temperature of -290° Fahrenheit (-180° C), though, we know that any liquid bodies can't consist of pure water. Methane and ethane, or a combination of the two, would be possible, however. Other data gathered by Cassini indicate the chemical composition of surface materials. Interpretation of these data seem to confirm the supposition that Titan is covered with hydrocarbons—organic compounds that may be similar to those that existed on earth before life evolved. By studying Titan, scientists may gain insight into how basic hydrocarbons develop into complex molecules that can lead to life. Titan has weather During the October flyby, Cassini observed a field of clouds, thought to consist of methane, near the moon’s south pole. Other than that, the Titan skies were curiously clear. Images taken during the December 13 flyby, however, show patches of clouds nearer to the moon’s equator, which is the first direct evidence that Titan has changing weather patterns. This new information will help scientists understand wind speeds and atmospheric circulation. An upcoming exploration of Titan’s atmosphere Data gathered in these two recent flybys will also aid the scientists responsible for the Huygens probe that will descend through Titan’s atmosphere in January 2005. Huygens , which hitched a ride aboard Cassini , has been dormant for the seven years long years of its journey. But it’s about to awake. Huygens separated from the Cassini orbiter in late December and began coasting towards Titan. On January 14 it will parachute through Titan’s atmosphere for more than two hours, collecting images, temperature readings, wind measurements, and pressure profiles. It will also analyze the chemical composition of the gases it passes through and any particulate matter the gases contain. This is of particular interest because the December 15 flyby revealed that the high haze, rather than being homogenous, is made up of many discrete layers. In addition, Huygens will be listening to sounds in Titan’s atmosphere. Should the probe pass through a storm, it might record audible emissions that indicate the presence of lightning, or the sounds of rain striking its surface. When Huygens reaches Titan’s surface, it could crash into ice, sink into a hydrocarbon snow, or possibly splash down into a methane lake. It’s unlikely that the probe will survive the landing, but scientists hope that Huygens will be able to transmit for a few minutes from the surface of this distant world.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

Before Cassini arrived on the scene, no Saturnian moon smaller than about 12 miles (20 km) in diameter had been discovered. Cassini’s improved imaging technology and its initial discoveries show that we have an exciting new capability for learning about tiny planetary satellites. If Cassini finds many new moons, it will test the theories scientists currently have about these small bodies and will expand our understanding of how small moons form and evolve.

- - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - - -

+ See a computer rendering of Cassini's current position in the rings of Saturn |

||||||||||||||||||||||

|

|||||||||||||||||||||||