Where and When You Can See the Transit

The 2012 transit will be visible, at least in part, over a large portion of the world. As the map indicates, in the afternoon of June 5 it can be seen in parts of the Americas, and in the morning of June 6 it can be viewed from most of Europe, eastern Africa, central Asia, and the Middle East. The entire transit can be seen from locations that include Northwestern North America, Hawaii, much of Asia, New Zealand, and eastern Australia.

The transit starts at about 22:09 Universal time (Greenwich mean time) on June 5 and ends at about 4:49 UT on June 6. NASA/Goddard Space Flight Center has prepared Circumstances for Cities tables so you can look up the transit times for particular locations. The times are in Universal time; you can convert to local time by using the World Clock—Time Zone Converter . (You may notice that the date given for the transit on the tables is "2012 June 06" rather than June 5–6. That's because the date is for Greenwich, England. Greenwich is at the prime meridian—0° 0′ longitude—and is the starting point of all the world's time zones.)

What You Can Observe

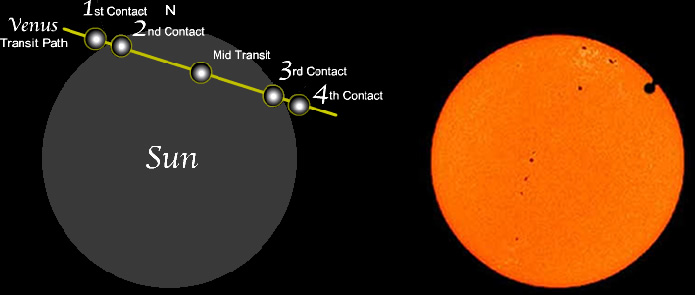

If you're watching the transit from the northern hemisphere, Venus will move from left to right across the upper half of the Sun at a slight downward angle. If you're in the southern hemisphere, Venus will move from right to left at a slight upward angle across the lower half of the Sun. (People in the southern hemisphere are "upside down" relative to people in the northern hemisphere, and vice versa.)

The transit starts with the

first contact,

when Venus's outside edge first appears to touch the outside edge of the solar disk, or

solar limb

. In less than 20 minutes, Venus will arrive at the second contact, when the planet touches the inside of the solar limb. The time between the first and second contacts is known as the

ingress

. A little over six hours later, the third and fourth contacts will occur, incorporating the

egress

. (The egress repeats the process of the ingress, only in reverse.)

If you're able to observe either the beginning or end of the transit with a telescope ( equipped with a special filter! ), you'll be able to observe something called the "black-drop effect": Venus seems to develop a smeared appendage as it enters and leaves the solar disk. The black-drop effect prevented astronomers from accurately timing Venus's ingress and egress; without exact times, their calculation of the astronomical unit (AU) , the distance from Earth to the Sun, was inexact.

For centuries, no one knew what caused the black-drop effect, although suggestions included the idea that Venus's substantial atmosphere was responsible. In 1999, however, NASA's Transition Region and Coronal Explorer (TRACE) observed the black-drop effect during a transit of Mercury.

This was significant because TRACE was beyond Earth's atmosphere, and Mercury has no atmosphere to speak of. It now appears that the black-drop effect may be due to limitations in telescopes, combined with the fact that the disk of the Sun appears darker at its edge.

Another thing to watch for as you observe the transit is a "halo" around Venus. Mikhail Lomonosov, a Russian scientist observing from St. Petersburg, noticed this halo during the 1761 transit. He proposed that the halo occurred because Venus had an atmosphere; he was later proven correct by the astronomer William Herschel.