|

September

12, 2004

It’s a two-day trip to the Galapagos for nearly all

the participants to this “usable science” workshop,

and we’ve come from all over the world to converge in

Guayaquil, Ecuador’s largest city. Introductions and

shop talk start immediately and I find a good mix of different

backgrounds: social anthropology, meteorology, economics,

agriculture science, public health, biology, philosophy, oceanography,

climatology, hydrology, and environmental science. A shared

journey seems a great way to start a meeting and perhaps that

was the deliberate plan of the organizer, Michael Glantz (or

as everyone calls him, “Mickey”). All the participants

were handpicked by Mickey for their expertise, richness and

diversity of ideas, and ability to think across disciplines.

After

spending the night in Guayaquil, we board another flight to

the Galapagos. From the air, this group of islands appears

dark and bare of vegetation. On the ground on Baltra Island,

we see our first iguana and some scattered prickly pear cacti

(

Opuntia echiosis

). A short boat ride takes us to

Santa Cruz Island, and a bus delivers us to our destination:

Puerto Ayora. With about 10,000 residents, it’s one

of the largest towns in the Galapagos.

We arrive

to scout out the meeting location, the Charles Darwin Research

Station just outside of town. The station was established

in 1959, the same year that Ecuador placed the Galapagos archipelago

under the protection of its national park system to commemorate

the 100th anniversary of the publication of

The Origin

of Species

. But we’re told by our liaison that

there’s a problem: We can’t meet at the research

station because Galapagos National Park employees were planning

to strike the next morning and shut down the research station

and park.

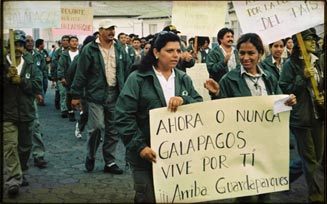

Of Fishermen, Sea Cucumbers and Politics

The park rangers were angry because the central government

in Ecuador had just fired the park director and were sending

in a replacement. I was told by Jose Luis Santos, an Ecuadorian

professor and co-organizer of the meeting, that this would

be the eighth director in the last year. The park employees

were tired of having their boss replaced every month or two

and were protesting the government’s appointment of

yet another new one. I asked Jose why the high turnover and

he said it was a political strategy to appease Ecuadorian

fishermen, who wanted rules for collecting in the park loosened.

What they are fighting over is the sea cucumber, a sausage-shaped

invertebrate highly prized in the Japanese market. The fishermen

want to collect year-round to keep their income flowing, but

park officials worry about the ecological damage such harvesting

would cause, and continue to enforce strict regulations. The

government, pressured by the fishermen and not wanting to

appear indifferent to their needs, reacts by firing the park

director. But each successive park director supports regulations,

so the cycle continues.

It’s

one of those seemingly intractable struggles between human

need and environmental peril, a subject we would return to

often during the course of the workshop; that is, once we

found a meeting place.

|