|

September

15, 2004

The science of this workshop is focused around the climate

phenomenon known as El Niño, or more formally ENSO

(El Niño Southern Oscillation). We heard from climate

forecaster Tony Barnston of Columbia University’s International

Research Institute (

http://iri.columbia.edu/

)

about the latest in El Niño forecasting and climate

prediction (NOTE: the audio stream for this session is not

available).

The biggest

news is that earlier in September, NOAA (

http://www.noaanews.noaa.gov/stories2004/s2317.htm

)

announced that a “weak” El Niño has developed

in the east-central tropical Pacific (

http://iri.columbia.edu/climate/ENSO/currentinfo/update.html

).

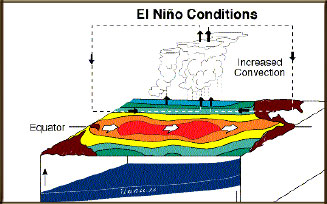

When climate scientists say weak, they mean that the warming

of sea surface temperature that characterizes El Niño

is relatively small. For this current El Niño, the

ocean temperature is an average of 1 degree Centigrade above

normal just to the east of the dateline in the tropical Pacific.

As this warmer water on the sea surface spreads eastward toward

South America, it can impact weather in the U.S. and around

the globe, creating wetter-than-normal or drier-than-normal

conditions (in California, we get higher rainfall in the winter

during El Niño years).

Predicting El Niño

This is a late-developing El Niño, Tony Barnston says,

and took many of us by surprise. Usually they pop up in late

spring and may persist for about a year. “My confession

is that we’re not good at predicting the onset of El

Niño but we’re pretty good at knowing about how

long they will last once they get started,” he says.

That’s fine for the U.S., which usually feels the impact

of El Niño six months after it develops. “But

people in India, Australia, and Africa’s Sahel desert

probably think we’re dumb because they start experiencing

impacts much earlier, from June through August, just as the

El Niño usually begins, and have no time to prepare.”

Why is

El Niño so hard to predict? It comes down in part to

the difference between weather and climate, Barnston says.

When scientists say weather, they’re talking about the

short-term changes in the atmosphere that lead to rain, wind,

clouds, and changing temperature on a day-to-day basis. Climate

is the long-term or seasonal average of temperature and precipitation

that happens over months or years. “We’re good

at weather forecasting, there are computer models that provide

lots of details about storms, winds, fronts, and pressure

conditions out to about five days in the future.” Predicting

climate is another matter. Longer-term climate conditions

are subject to many factors working together, and the system

is very sensitive to initial conditions. That means that a

small change in atmospheric pressure, wind patterns, or ocean

temperatures and currents can have a large impact on weather

for any particular day in the future beyond the fifth day.

Still, knowing about likely changes in seasonal average temperature,

rain, or snow patterns is very useful for farmers, water and

utility companies, and folks thinking about repairing their

roofs. That makes scientists like Tony Barnston accountable

to people on the ground (or “users” in the vernacular

of this workshop), motivating many in the field to develop

more accurate climate forecast models and to make their results

more understandable and useful to the public.

Impacts

of El Niño

After getting a handle on what El Niño is, the rest the day

was spent talking about what El Niño does. Scientists estimate

that 25% of the earth’s land surface is affected by

El Niño in some way or another. Here is a sampling of some

of the impacts:

-

Increased cyclone activity in tropical Pacific Islands

-

Drought in parts of Australia affecting farming

-

Collapse in fisheries in eastern Pacific, off the coasts

of Peru and Ecuador

-

Micronesia has a combination of droughts and floods

-

Rice crop in the Philippines can see much lower yields

-

In flooded areas, health effects include more possibility

of mosquito-borne diseases, and lack of fresh crops affects

nutrition.

|