|

Microscopic

denizens of a typical backyard can transform kitchen scraps

into paydirt.

by

Mary Miller

|

|

A

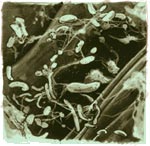

leaf enlarged 5,000 times, with decomposers at work. The

round and oval shapes are bacteria; the threadlike structures

are fungal mycelium.

|

Every

morning after he’s brewed the coffee, my husband, Jeff,

dumps the grounds into a bowl of kitchen scraps and heads

into the backyard—but not toward the trash can. Instead,

the vegetable scraps, coffee grounds, and eggshells go into

a green plastic structure about the size and shape of a doghouse

in a corner of the yard near my vegetable garden.

Jeff

removes the "roof" of our compost bin and tosses

the morning’s refuse on top of a pile of grass clippings

and shredded twigs. Once a week, he mixes and turns the pile

with a pitchfork and spritzes it with water. Sometimes on

cool mornings, I can see steam rising out of the little green

house, a sign that my pile of rot is alive and well. In a

month or so, the decomposed debris will be ready for working

into my raised vegetable beds, where it will perform its magic

on my tomatoes and peppers.

Before

we started gardening, the compact, bricklike clay soil in

our backyard supported only crabgrass and a few stray weeds.

Plants grow best in soil that has a balance of clay and sand,

so one of the first things we did was order a truckload of

sand and fine topsoil to mix into our garden soil.

Because

plants must have nutrients, I knew that we also needed to

feed the soil with humus, or organic material. We bought bags

and bags of steer manure and mushroom compost and spread it

on top of the soil, but I soon tired of lugging stinky cow

poop home from the garden store. So I began making my own

humus in the form of compost—decomposed dead plants.

Decomposition is nature’s way of recycling nutrients;

I help the process along by providing food and shelter for

a balanced ecosystem of compost critters, including scavengers,

predators, and decomposers.

Life

in the Compost Bin

|

Recipe

for compost:

Recipe

for compost:

Choose

from the following ingredients, keeping a balance between

green matter and brown matter—bread, coffee grounds,

eggshells, garlic skins, grass clippings, dead leaves,

shredded newspaper, spinach, strawberries, chopped-up

twigs, wood chips, and beans and rice. Substitute freely.

Add soil, moisten with water, and mix well. See below

for more information on

making compost

.

|

Much

of the heavy decomposition of kitchen scraps and yard trimmings

is performed by microscopic actors: actinomycetes and other

bacteria, protozoa, and fungi. I asked Kate Scow, associate

professor of soil science and microbial ecology at the University

of California at Davis, to describe the action. "You

start out with these big chunks of plant material," she

says. "There’s no way plants can use them in that

form." She explains that the fungi and actinomycetes

break up the big pieces of garbage into smaller chunks. Simple

bacteria finish the job by digesting these small pieces into

their chemical components: nitrogen, carbon, phosphate, and

other plant nutrients.

Of

the soil decomposers, bacteria are among the most important

and abundant. A pea-sized clump of garden soil can contain

a billion bacteria. If you looked at them under a good microscope,

Scow says, "you wouldn’t see anything that’s

terribly exciting—lots of little boring rods, spirals,

and spheres. Bacteria all look pretty much the same. It’s

what they do that’s fantastic. They can make a living

on just about everything on the planet. You can have the same

little rods, and one of them will live off inorganic iron,

another one will break down sugar, and another one will fix

nitrogen."

Plants

need nitrogen to make proteins and grow new tissue. Although

nitrogen is plentiful in the air, it’s in a form that

plants can’t use. Certain bacteria fix, or convert, nitrogen

into a form that plants can take up in their roots. This is

a metabolically expensive procedure for the microbes, requiring

lots of carbon for fuel, and most of the nitrogen-fixing bacteria

live in a symbiotic partnership with certain plants such as

beans and other legumes.

The

bacteria live inside special plant structures called nodules

on the roots of legumes. The plants provide carbon for the

bacteria, and the bacteria release excess nitrogen for the

plants. To bring up the nitrogen levels in their soil, farmers

and home gardeners often rotate bean crops in different places

every year. Extra nitrogen, leaked from the legumes, helps

nourish the following crop.

When

you hoe your garden and notice a rich, earthy smell, you’ll

know that actinomycetes are at work. Chemicals given off by

the actinomycetes are largely responsible for this characteristic

odor. They live deep in the soil near the plant roots, where

they convert dead organic matter into a peatlike substance.

Actinomycetes, which compete for resources with other bacteria

in the soil, conduct a kind of biological warfare: the actinomycetes

produce their own antibiotics, chemical substances that inhibit

bacterial growth.

Other

prominent microscopic denizens of the soil are the fungi.

Soil fungi are related to the mushrooms that grace our dinner

table and the molds that invade our refrigerator. Fungi, once

considered primitive plants, are now classified in their own

kingdom. They lack chlorophyll and cannot manufacture carbohydrates

from photosynthesis as plants do. Most of the life of a fungus

is spent underground, where it forms a bundle of strands known

as mycelium, a string of simple cells that produce digestive

enzymes and acids. These chemicals, which can break down the

toughest wood fibers, give fungi the ability to eat just about

anything.

Fungi,

bacteria, and other decomposers break down garbage into fertilizer,

but they don’t willingly release those nutrients into

the compost and soil. "That’s where the importance

of the microbe predators, the arthropods and nematode worms,

comes in," Scow says. "They essentially bust open

the guts of the microorganisms."

Fungi,

bacteria, and other decomposers break down garbage into fertilizer,

but they don’t willingly release those nutrients into

the compost and soil. "That’s where the importance

of the microbe predators, the arthropods and nematode worms,

comes in," Scow says. "They essentially bust open

the guts of the microorganisms."

Only

recently have experts come to appreciate the critical role

predators play by liberating the pool of nutrients stored

inside the bodies of microbes and making those nutrients available

for plants, Scow adds. Important predators include mites,

sow bugs, springtails, and nematodes. Soil mites, arthropod

cousins of the tick, live their entire lives underground feeding

on plant matter, nematodes, fly larvae, other mites, and springtails.

Sow bugs, which have a roly-poly shape and an armor-plated

body, eat decaying vegetation.

Nematodes

look and move like very tiny eels, thrashing from side to

side to move through their soil environment. These tiny predators—smaller

than the period at the end of this sentence—seek out

living bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and other nematodes in the

compost. In the soil, a few species of parasitic nematodes

can also wreak havoc on the roots of living plants by sucking

all the juice from them.

Nematodes

look and move like very tiny eels, thrashing from side to

side to move through their soil environment. These tiny predators—smaller

than the period at the end of this sentence—seek out

living bacteria, fungi, protozoa, and other nematodes in the

compost. In the soil, a few species of parasitic nematodes

can also wreak havoc on the roots of living plants by sucking

all the juice from them.

But

as in all healthy ecosystems, the compost pile has checks

and balances. Living among the rotting banana peels and liquefied

veggies are certain fungi that are natural-born killers of

the sometimes harmful nematodes. These predatory fungi snare

the nematodes by casting a net of sticky fibers. When the

wiggly worm blunders into the net, it sticks like a fly to

flypaper, and the fungus grows new tendrils to completely

envelop and eventually dissolve and absorb the nematode.

My

all-time favorite compost critter is the earthworm. I love

earthworms so much that I bought a box of red worms (a relative

of the garden-variety field worm) to add to my compost bin.

More than 1,800 different earthworm species exist worldwide,

including a ten-foot Australian specimen with a three-inch

girth that weighs a couple of pounds.

Darwin

himself took a fancy to earthworms and wrote an entire volume

on the benefits of earthworms to the soil. The earthworm,

little more than a digestive tube surrounded by skin, is a

veritable humus factory, taking in garbage and leaving its

droppings, called castings, which are rich in nutrients. The

earthworm is nature’s plow. As earthworms burrow and

move soil around, they open up pockets of life-giving oxygen

and make room for plant roots to penetrate.

Darwin

himself took a fancy to earthworms and wrote an entire volume

on the benefits of earthworms to the soil. The earthworm,

little more than a digestive tube surrounded by skin, is a

veritable humus factory, taking in garbage and leaving its

droppings, called castings, which are rich in nutrients. The

earthworm is nature’s plow. As earthworms burrow and

move soil around, they open up pockets of life-giving oxygen

and make room for plant roots to penetrate.

In

winter and early spring, when it’s wet and cool, the

earthworm population explodes, and I see thousands of little

pink bodies wiggling through the compost. According to Kate

Scow, earthworms are a good sign. "As long as you can

see the big guys, your compost is doing okay," she says.

"You won’t have earthworms unless things are going

well."

Turning

Rot into Brown Gold

For

four years, I have focused on the care and feeding of my population

of microbes, scavengers, and predators, and I’m proud

to say that I’ve got a really good pile of rot going.

I’m continually amazed at the work they do. Into the

compost bin go slimy gobs of goo that once were salad greens,

along with dead leaves and fresh grass clippings. Out comes

a crumbly, brown material that smells like a walk in a forest.

I used to feel guilty about abandoning leftovers in the back

of the refrigerator while I ate take-out Chinese food, but

I now have an easy out. The zucchini that grew to frightening

proportions in the garden and the mold-covered bowl of rice

go back into the soil instead of to the local dump. But the

benefits go far beyond simple guilt relief.

Compost

is like a gift I give to my garden. In return, it produces

beautiful peppers, tomatoes, and herbs every year. Compost

improves soil structure by breaking up clay particles and

binding together particles of sand. It also aerates, improves

drainage, and prevents soil erosion. When added to soil, compost

neutralizes toxins, holds precious moisture, and feeds beneficial

soil microbes with a steady diet of carbon, the precious secret

ingredient of compost.

All

too often, Kate Scow says, conventional farmers and gardeners

overlook the importance of adding carbon to their fields and

gardens. "People don’t think about how carbon drives

all the other nutrient cycles in the soil," she points

out." It’s the underpinning of the entire system.

The bugs that make nitrogen and phosphorus available to plants

need carbon for fuel."

There’s

even some evidence that compost promotes plant health and

helps prevent disease, Scow adds. "There are some studies

showing that a really active microbial biomass will shut out

detrimental organisms, possibly just through competition for

nutrients," she says. Some microbes also secrete toxins

to prevent disease organisms from spreading in the soil. Scow

notes, too, that some microbes may produce growth factors—chemicals

that promote plant growth.

As

the carbon in compost is broken down by soil microbes, nutrients

are slowly leaked into the soil and taken up by plants. This

steady trickle of nutrients is preferable to the boom-and-bust

approach of applying chemical fertilizers because it lasts

all growing season and doesn’t periodically flood the

plants with excess nutrients that can damage and even inhibit

plant growth.

Beyond

those practical applications, however, having a compost pile

can become its own reward. I started out thinking that it

was just a neat way of recycling kitchen scraps and dead plants.

But somewhere along the way, things got turned around, and

now I’m focused as much on feeding my compost pile as

I am on feeding my garden. Kate Scow expresses a similar sentiment:

"Sometimes I feel that what I’m farming for is the

waste for my compost."

Making Compost

First,

you need a compost bin. We bought a prefabricated bin

from the local garden supply store, but you can also

build one out of plywood and chicken wire, dig a pit

in the ground, or even use a plastic garbage bag or

a garbage can with holes poked in the bottom, top, and

sides for drainage and aeration. (If you’re using

a plastic bag, you should leave it open every other

day to let air in.)

A

simple recipe for starting compost is to layer one-third

dry (brown) material, one-third green vegetation, and

one-third soil. (Soil provides a starter supply of microbes

to get the compost going.)

After

that, almost anything goes: kitchen waste, grass clippings,

dry leaves, dead plants, coffee grounds, shredded newspaper,

and even clothes-dryer lint and pet hair. When adding

ingredients, you should strive for a twenty-five–to–one

ratio of carbon sources (brown stuff like dead leaves

and newspaper) to nitrogen sources (green stuff like

grass clippings and foliage). Green materials contain

carbon as well as nitrogen, but dead leaves and other

brown materials are largely devoid of nitrogen.

Manure

is an excellent compost ingredient if you can get ahold

of it. Cattle, horse, and chicken manure work well,

but avoid pet and human wastes, as they may spread human

diseases.

Other

materials to avoid are bones, meat, or fat, which often

smell bad and will attract rats and other pests to your

pile. Don’t compost weeds or diseased plants, or

you may reintroduce the weed seeds or diseases into

your garden.

To

give your compost a head start, chop up or shred materials

before adding them to the bin. You might consider buying

or renting a mechanical chipper/shredder if you have

large branches to compost.

Periodically

sprinkle the pile with water so that it stays moist

but not soggy—it should be about as damp as a moist

sponge. With a pitchfork or spade, turn or stir the

compost to introduce air. A pile that is too wet or

isn’t exposed to enough oxygen can turn stinky.

An easy cure for this problem is to open the container

and let the compost dry out for a couple of days.

For

more information, "The Rodale Book of Composting,"

edited by Deborah L. Martin and Grace Gershuny and published

by Rodale Press, is an excellent and detailed how-to

manual.

<<Back

to top of main article

|

--------------------------------

This

story originally appeared in the Gardening issue of the "Exploratorium

Magazine."

EXHIBIT

SECTIONS

:

The Stuff of Life

,

Life Needs Energy

,

Making

More Life

,

Change Over Time

©

Exploratorium

| The museum of

science, art and human perception|

Traits

of Life

|