|

|

Image

courtesy of David Goodsell.

|

|

Art

and Science combine to image what cannot be seen.

An

interview with David Goodsell by Mary K. Miller

David

Goodsell is a molecular biologist and associate professor

at Scripps Research Institute in La Jolla, California. His

lab researches drug resistance in HIV, which involves studying

both the structure and function of molecules involved in the

disease. With funding from the National Science Foundation,

Goodsell also writes and creates the illustrations for a column

called "

Molecule

of the Month

" for the

Protein

Data Bank

, an archive of the 3-D protein structures of

18,000 different molecules. This resource is used by structural

chemists, biomedical researchers, geneticists, and educators.

Professor

Goodsell has also had a lifelong passion for art. His paintings,

drawings, and computer-generated illustrations of molecules

and cells have been displayed in galleries and featured on

the covers of magazines and science journals. Goodsell’s

illustrations are based on scientific data from a variety

of sources, including scientific papers, micrographs of individual

molecules, and information about molecular structures gained

from X-ray crystallography. His representations of cells are

both accurate and beautiful. He is the author and illustrator

of several books, including the upcoming "Bionanotechnology:

Lessons from Nature" (Wiley and Sons, 2002).

Goodsell’s

artwork is featured in the "

How

Does a Muscle Work?

" poster.

Mary

K. Miller:

Your artwork opens a new world, something that

can’t really be seen even with a microscope. How much

of this new view is artistic interpretation and how much is

scientific data?

David

Goodsell:

We’re at a stage in the science where a

lot of the major molecular structures are known, but there

are gray areas. Probably two-thirds of the molecules’

structures are known. For the others, I have to speculate

about their size or even the fact that they exist. When I

draw these pictures, I try to imagine what it would be like

inside a cell with molecules and other structures close to

their proper shapes and dimensions. I think this adds more

complexity and maybe a little more realism than previous pictures.

When other people have attempted to draw cells at the level

I’m doing, they simplify things by using circles and

triangles to point out areas of uncertainty. I’ve resisted

that because it breaks the illusion that this is a photograph

or a direct representation. When I made that decision, it

opened the possibility of errors being introduced, but most

of my scientific colleagues understand why I’m doing

that.

Miller:

Is it an aesthetic or scientific choice to

add that realism to your illustrations?

Goodsell: That definitely comes from science. It’s just

in the past decade or so that we’ve been able to do that

because we have so many known structures. But the real challenge

is that when I draw one of those pictures I go to each individual

reference, pull out each individual structure, and combine

them all.

Miller:

Do you consider your computer-generated images as artistic

or aesthetically pleasing as your painted or hand-drawn pictures?

|

|

|

|

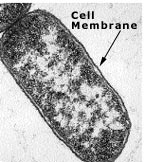

Goodsell

combines information from many sources to create illustrations.

He starts with electron micrographs. Here is a transmission

electron micrograph (TEM) of an Escherichia coli bacterium,

magnified 120,000 times.

|

G

oodsell

then looks for molecules’ individual structures.

On the left (above) are proteins, bound within the cell

membrane, that are involved in energy production. The

molecules in the center are involved in protein production.

On the right is a DNA strand with several proteins involved

in reading genetic information.

|

Finally,

Goodsell places all the structures in the proper places,

creating an image of the cell showing all the molecules,

such as in this illustration of an E. coli bacterium.

|

|

Micrograph

courtesy of University of California, Berkeley,

Department of Molecular & Cell Biology,

Instructional Laboratory Program. Illustrations

courtesy of David Goodsell.

|

|

Goodsell:

I try to blur the line between the two. In my computer pictures

I go for a style that is reminiscent of my hand-drawn style

and vice versa. That being said, I certainly put a lot more

of myself into my paintings and hand-drawn pictures. The paintings

also contain more speculation than the computer pictures.

The computer renderings are based directly on data and could

be used for anything from a textbook to a general science

magazine to a journal article. Because there is more speculation

in the paintings, they’re used more as an introduction

rather than to explain something directly.

Miller:

Most people think that science and art operate in completely

different realms, but you manage to combine them. Does the

combination of art and science together contribute more to

your pictures than either alone would do?

Goodsell:

One thing I’ve noted is that scientists and artists are

different. When I go to a scientific conference, the scientists

tend to be very confrontational. Everyone is questioning your

results, which is the way science works. If your results don’t

make it, there was something wrong. When I go to artistic

conferences, everyone is walking in with their approach to

the subject and they tend to be much more supportive. There

isn’t as much questioning because it’s more of a

personal interpretation of what you’re doing.

In

my own work, the combination of art and science gives me a

way to access the wonder of nature. It makes me really look

at results and think about them in a deeper way. The thing

that drives me continually is the beauty of these objects

that I’m working on and being amazed at how unusual they

are. That’s something most scientists don’t spend

much time on, coming up with ways to display their work that

captures their excitement about science.

Miller:

In your scientific work, what is the relationship between

form and function in understanding how proteins and other

biological molecules work?

Goodsell:

It’s like understanding any piece of machinery. You have

to know what it looks like and how its different parts interact

with other parts, the other molecules. The study of structure

also allows us to go in and make changes. For instance, in

my HIV research that’s exactly what we do—we look

at the structure of one of the viral proteins called protease.

Protease cuts other proteins into pieces, a key step in the

ability of HIV to mature in the cell. Because we know the

structure and function of protease, we can design a new molecule

that will go in and block its ability to chop up other proteins.

That’s where the

Protein

Data Bank

comes in handy—for finding molecules that

have specific shapes and functions. There are all kinds of

different molecules in there, some of which are very useful.

Miller:

In your books and in your Web column, you seem to also have

developed your literary talents. Is writing for the general

public something that’s difficult for a scientist?

Goodsell:

Most scientists, it’s true, are hopelessly mired in jargon.

It’s useful for communicating with people who are in

the same field. For me, writing for a broader audience is

much more recent, starting with my books. I was really lucky

to have a mentor in this at UCLA, Richard Dickerson, who was

my graduate advisor. He has a long history of really taking

the time to think about who he’s writing for and encouraging

his students to do the same. It’s a real challenge, trying

to reach a general audience, but it’s really, really

satisfying.

Miller:

Do you consider it a bigger achievement if one of your paintings

lands on the cover of American Scientist magazine than if

one of your scientific articles were appearing inside the

journal?

Goodsell:

I’m more proud of my pictures, because they’re an

expression of me. Dick (Dickerson) who I learned everything

from, once told me that as a scientist you have to divorce

your feelings from your work, so you can stand up to criticism

and not take it personally. I try to exercise that with all

of my research, but I don’t do that with my pictures.

They are uniquely me, and when someone makes a comment about

them they’re making a comment about my aesthetics. They

are closer to an expression of what I feel.

Miller:

Any last thoughts?

Goodsell:

Just the general concept that people are starting to think

more about art and science together. My science colleagues

are much more likely to go to an artist or illustrator to

present their work and artists are going more and more to

scientists to understand these concepts and fold them into

their own work. Artists want to understand more about the

research because there are real implications for society and

they want to comment on that and make the issues clearer for

the public. So the lines are blurring, or at least the sides

are more and more willing to talk. It’s an exciting time

for all of us.

-------------------------

This

story originally appeared in the Cells issue of the "Exploratorium

Magazine."

EXHIBIT

SECTIONS

:

The Stuff of Life

,

Life Needs Energy

,

Making

More Life

,

Change Over Time

©

Exploratorium

| The museum of

science, art and human perception|

Traits

of Life

|